I am not a small person, despite not reaching my predicted height of 6’4". (My Mum was told by a nurse that if you doubled a child’s height at the age of two, that would be their adult height. Goodness knows what the shoe size calculation would have been.) As a result of being tall, always in the middle of the back row in school photos, I am aware of taking up space. This is not in a dysmorphic way - I love being tall - just simply that I always feel there is ‘some there there’, to paraphrase Gertrude Stein. As a result, I do not cope well with dinky rooms, small doors, low ceilings, and little thatched cottages; when I lived in Bristol I loved the high ceilings and huge rooms in the early/mid C19 houses which had been turned into beautifully proportioned but cold, draughty, none-too-clean student flats.

I’ve been thinking about taking up space, in particular women taking up space, for a little while. We went to see the recent Megan Rooney exhibition at Kettle’s Yard (in fact I went three times). I knew nothing about her work beforehand, and was enthralled by the site-specific painting she had created - in many ways simply because it was unexpectedly enormous, huge, unmissable. She’d covered all four walls of one of the rooms with fabulous colours which reflected the weather and conditions of the eighteen days in early summer when it was being painted. The paint was still smelling fresh when we first went, and the room felt like a cross between an artist’s studio and a gallery. I loved the scale, the ambition, the fact that she needed a fork-lift to reach the higher sections. (Now that the exhibition has finished this mural has been painted over - quite a radical thing to do.)

[‘Folies Bergères’ (2024) by Flora Yukhnovich]

As with the two very big, very fabulous semi-abstract Rococo paintings by Flora Yukhnovich I saw recently at the Wallace Collection (what would I give to have these printed on fabric and made into curtains), there is nothing dainty, diminutive, or delicate about this filling up of all the available space. It is the antithesis of what a lot of women’s creative output has traditionally been: polite, small-scale, tiny works, exquisite embroideries, twenty holes or stitches-to-the-inch needlepoints and quilts, intricate, time-consuming stumpwork and miniatures. Rather like Jane Austen who, not long before her death, described her writing as being done with a fine brush on a "little bit (not two inches wide) of ivory". In the same letter to her nephew James she asked, “What should I do with your strong, manly, spirited sketches, full of variety and glow?”

[big flowers, big squares, big quilt]

What, indeed? It is precisely these elements of strength, spirit, variety, and glow which make me want to go large with my own stuff, and appreciate others who do.

[at ‘Sheila Hicks: Off Grid’, The Hepworth, Wakefield, 2022 ]

It’s fantastic when women make or paint pieces which, in order to take them in, require you to stand back and perhaps use a person for scale (Simon is very useful, and surprisingly good at co-ordinating/blending in with the art). Even when I don’t necessarily like the actual work, I can still enjoy something which proclaims its existence, is big, bold, in your face, or however you wish to describe it, and am delighted when female artists take up space and make themselves seen.

[‘Three Billboards Outside Tin Brook, Stockport’ with artist Helen Clapcott (2022)]

What Helen Clapcott did when made miserable by Covid lockdowns was brilliant, confident and, for her, out of character (although she did tell me at the Private View of her exhibition in Stockport that she’d always wanted to do something like this). Normally she works on a tiny scale with Jane Austen-style fine brushes but, inspired by the film Three Billboards Outside Ebbing, Missouri, she paid for three of her paintings of Stockport to be blown up and pasted on huge billboards. This is a wonderful example of a female artist almost shouting FFS I AM HERE! and breaking out of the constraints of the miniature.

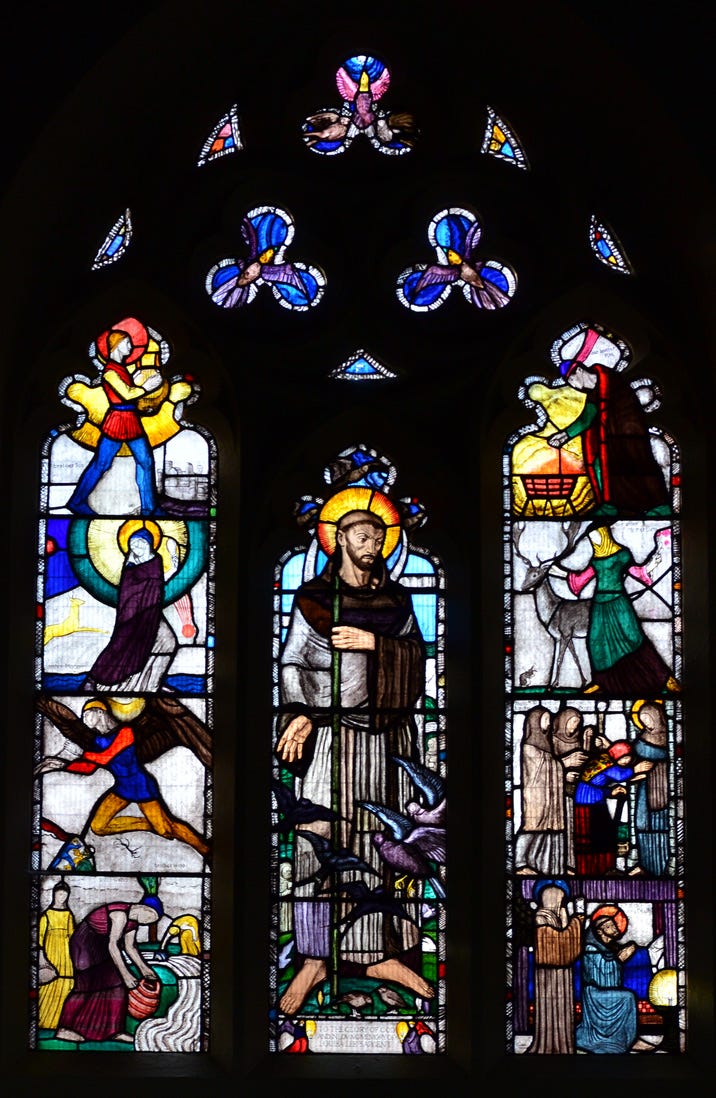

Writing my book on stained glass (2018) started me thinking about quite seriously women who are more than happy to take up space. From the mid-C19, there are so many female stained glass artists whose work is not acknowledged or properly known it’s really quite shocking. But I could see why they might take up this medium and make enormous pieces of work which are on permanent display in public buildings and seen by people on a regular basis. As such, windows are a gift to a professional artist/designer/maker who wants to be visible. This means that you can go into cathedrals and churches all over the UK and discover stunning, colourful, grand-scale works by female artists.

One of my favourites is Theodora Salusbury (1875-1956) who designed huge, brilliant, almost psychedelic explosions of colour and figures in churches in Leicestershire and Warwickshire. Almost nothing is known about her life and she asked for her studio papers to be destroyed after her death, yet her maker’s mark was a peacock, a tiny signature in the corner of a window, always different, but always a peacock. This suggests to me that, despite her quiet, private life, she was actually very knowingly showing off all her skills and artistry in a highly extrovert, public way. And she was not the only one, as I found out.

[Wilhelmina Geddes window (1930) in St Michael and All Angels, Northchapel, Wesr Sussex]

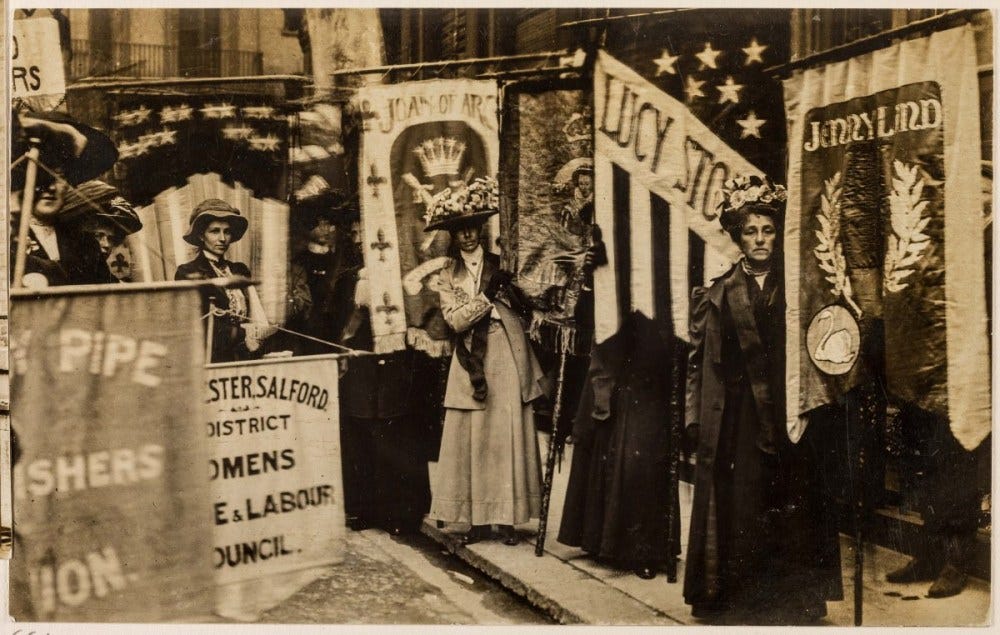

There are many, many more female stained glass artists, including the brilliant Mary Lowndes, who not only designed enormous church windows, but was also a leading light in the fight for votes for women. She founded the Artists’ Suffrage League in 1907 and designed many of the banners for the Women’s Suffrage March and Mass-Meeting in June 1908.

There’s an intriguing overlap between women’s stained glass windows and these banners which are also highly visible, take up space, and proclaim a message loud and clear. Quite a number of early C20 female stained glass designers were involved in the suffragette movement, and clearly they could see that mass communication required massive means of communication.

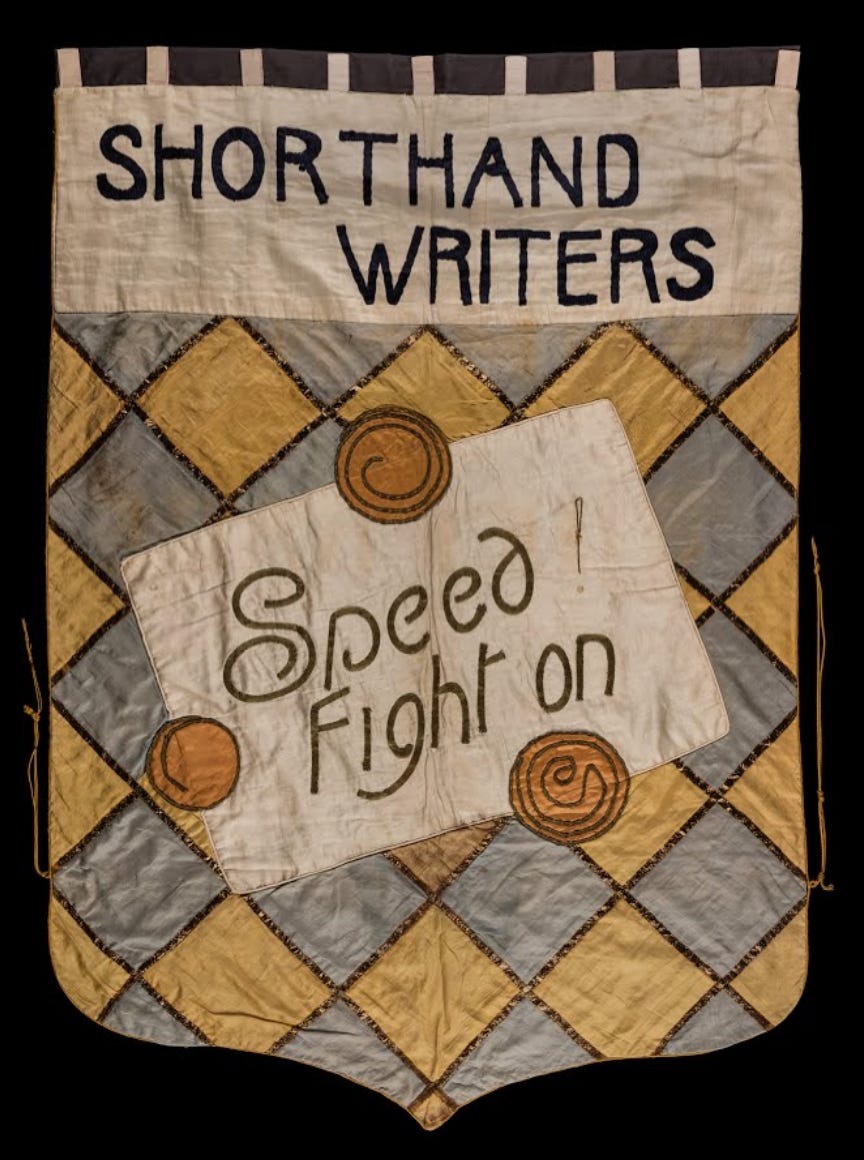

[Shorthand Writers suffrage banner, 1908]

Both windows and banners are beautifully made with clarity and visual impact so that they could be seen from a distance (and show up well in newspaper photos).

[Jane Austen writ large, suffrage banner, 1908]

Mary Lowndes wrote a pamphlet, Banners and Banner-Making (1909) which today is as pertinent as ever.

[Forest Hills, NYC, 1964]

Because banners take up space and are always a brilliant way for women to signal a message.

Happy Sunday!

PS there are many more artists I could include eg Barbara Hepworth, Joan Mitchell, Lee Krasner, Bridget Riley, Cornelia Parker, Paula Rego, Maggi Hambling to name just a few.

Interesting post. See the work of Annie Mulholland for a current stained glass artist in this great tradition. https://anniemulholland.com/about/

As a fellow StopfordianI, Helen Clapcott's paintings bring back memories of Stockport as it was. Before reading your post I didn't know about her. Unfortunately I won't be able to see the exhibition, as I live in France, but I shall look out for her work in future. Thanks for the discovery Jane.