[Leigh Road Gasholder, East Ham, photo by Francesco Russo because mine are taken from the car and are terrible]

When we drive to South East London, I’m not excited not only to see the big Brockets and now the Brocklet, but also the huge Leigh Road gasholder which can be glimpsed from the North Circular. You need to not be driving to have a good look at this wondrous piece of Victorian lattice ironwork, once the exterior of the holder which stored gas for thousands of homes and streets. It looks particularly impressive and evocative at dusk or in the depths of winter, which is exactly when those homes and street lamps needed their gas the most.

[Etruria Canal, 1920s, by William Blake]

I’ve grown to love gasholders, and am sad to discover that this is bad timing on my part, as so many are being dismantled now that they have no function other than to be huge, beautiful, elegant, intricate relics of a bygone era when gasholders of innumerable different designs - many remind me of Meccano structures - and sizes were at the cutting edge of domestic energy supply. Many towns like Etruria had their own gasworks producing what was known as ‘town gas’ where the booster pump would have to be used to cope with times of heavy demand as people did not want their lights to dim or the Sunday lunch to take ages to cook.

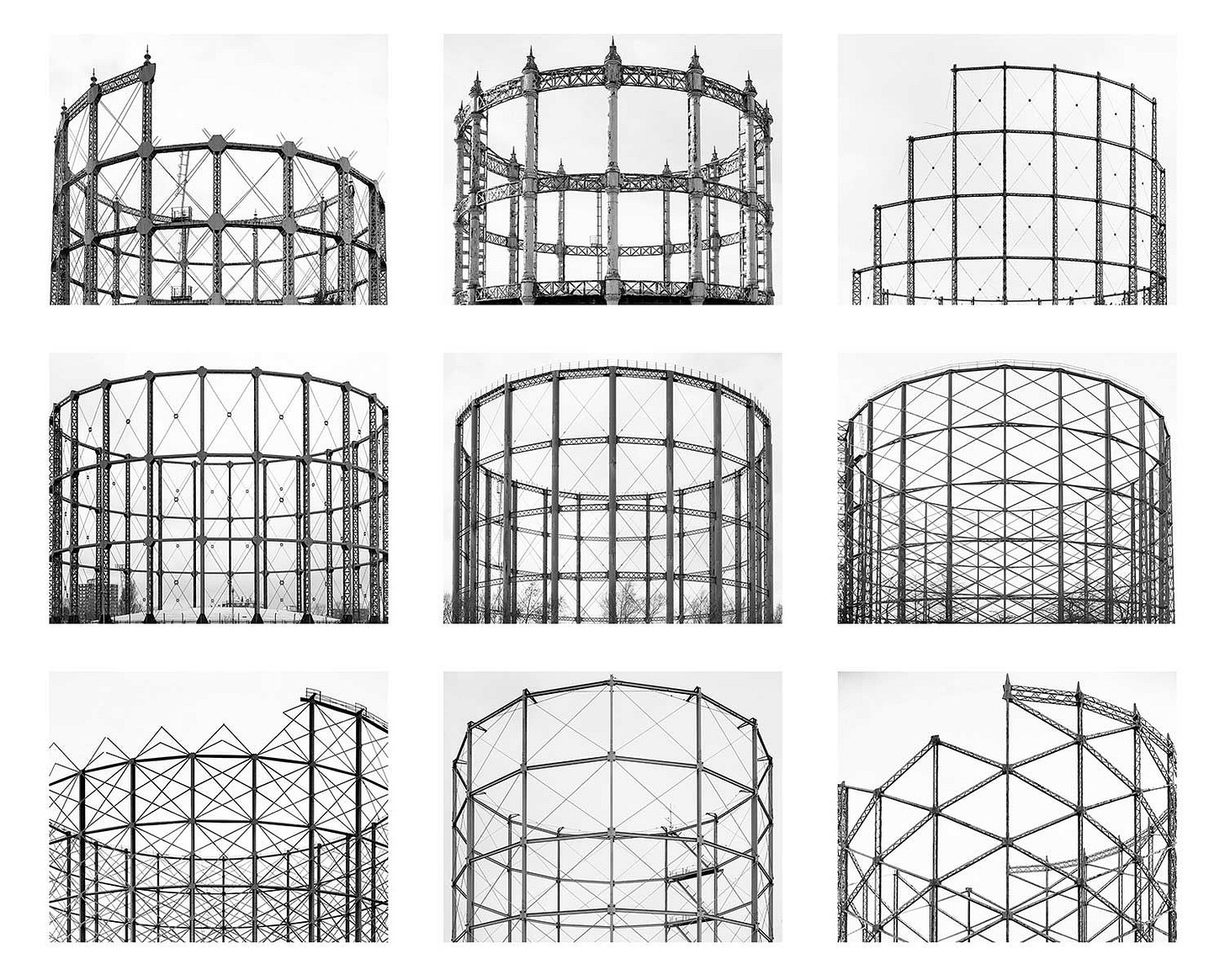

[‘Gas Tanks’, 1965-2009, by Bernd and Hilla Becher]

[Gasholder Grid 2, March 2022, by Richard Chivers]

Quite a few gasholders are now listed, but it’s a race against time to protect more. Like Francesco Russo, Richard Chivers has been documenting gasholders for a few years in a way which recalls the ground-breaking work of Bernd and Hilla Becher who photographed disappearing industrial architecture, including spherical and column-guided gasholders. His photos capture the gradual dismantling and then total disappearance of several well-known examples, and are graphic illustrations of the lack of recognition in many places that these wonderful structures receive.

[‘Salisbury Cathedral’ (1935) by Charles Ginner]

Chivers is one of many artists who have acknowledged the magnificent presence and everyday significance of gasholders. Charles Ginner actually moved Salisbury’s gasholder to be closer to the cathedral in his painting. It’s now gone, but if the ruins of Coventry’s medieval cathedral or St Luke’s Bombed Out Church in Liverpool can be kept and incorporated into the urban landscape, then why not more gasholders?

Their staying power is illustrated in a window by one of my favourite stained glass artists, Hugh Easton, whose subversive, gay glass is quite unique. His post-war window in St Dunstan and All Saints in Stepney was put in after the earlier glass was destroyed by bombs. The Lowry-esque panorama of the almost obliterated Stepney skyline was probably done by the studio of Hendra and Harper of Harpenden which employed exceptionally skilled glass painters; however HE never gave them full credit, so they took matters into their own hands and hid messages in windows saying that they’d done all the hard work. They knew their art references, too.

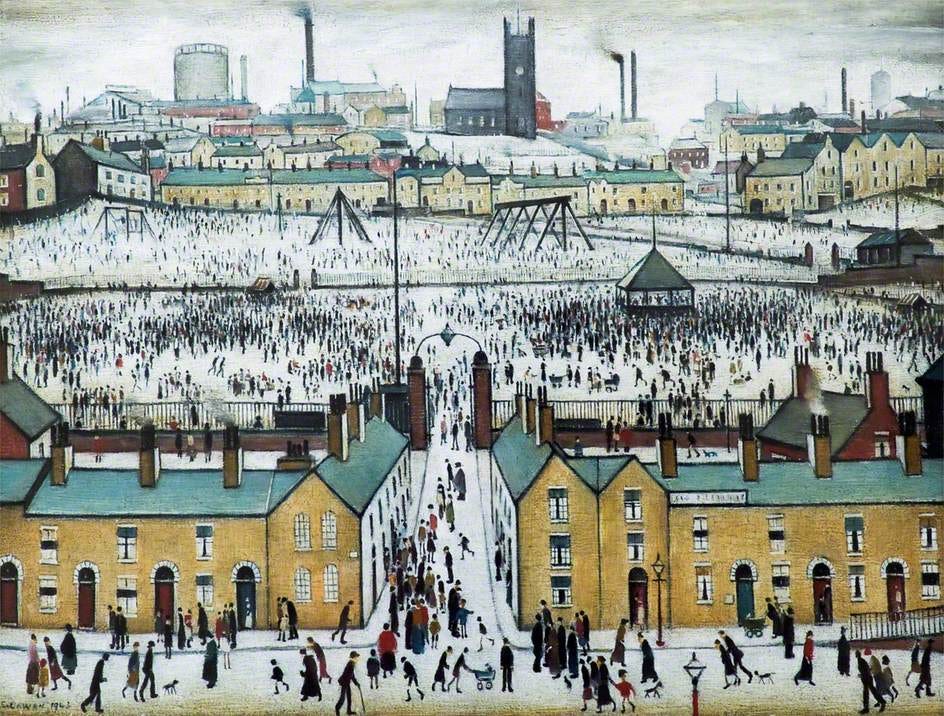

[‘Britain at Play’ (1943), by LS Lowry]

Looking again at this Lowry painting, the similarity is striking.

Councils and developers are too quick these days to pull down strong, sturdy Victorian cast-iron gasholders instead of looking at adaptive reuse solutions. I like this poem, ‘Gasometer’, by Edwin Morgan (1920-2010), in which he pleads for a stay of execution:

You don’t care about the wildness of the sky,

my old gasometer! The kitchen window

frames your gaunt frame, the black cross-struts

stand firm, stand out…

…Yours is the art of use.

You could be painted, floodlit, archeologized,

but I prefer the unremitting stance

of what you were in what you are, no more.

You are an iron guard or talisman,

and I hear that those who talk of eyesores

you have consigned, bless you, to the bad place.

Day of tearing down, day of recycling,

wait a while! Let the wind whistle

through those defenceless arms and the moon bend

a modicum of its glamorous light upon

you, my familiar, my stranded hulk – a while!

[the “gaunt frames” and “black cross-struts” which make gasholders such excellent subjects for cyanotypes - this is one of mine]

I’m sure it’s not beyond the wit of planners and developers and imaginative architects to come up with alternative uses. Russo suggests open-air theatres, greenhouses, and swimming pools. I think they’d make good climbing frames, modern amphitheatres, mini running tracks, circular tennis courts, art galleries for panoramic tapestries.

In fact, some are being converted to housing, with dwellings inside the old frames. If you have time to spare before getting a train from King’s Cross, it is worth walking beyond Granary Square and Coal Drops Yard to have a look at Gasholder Park and the Gasholders housing development in the ‘Triplet’ (three conjoined gasholders).

[Workers at the Gas Light and Coke Company at Bromley By Bow, London, on top of a gasholder, 1918]

It would be nice to think it’s possible to recreate this tea-break scene on the roof terrace of one of the penthouses (asking price £2.95 million, or duplex for £7.5 million).

[Fakenham Gasworks Museum]

Or it is possible to simply leave the skeletons as monuments to an industrial age. Earlier this week we went to the Fakenham Gasworks Museum which is probably way down most people’s lists of summer holiday attractions, but let me tell you it was buzzing and busy when we were there, full of people recognising a familiar, faintly sulphurous smell and reminiscing about gas appliances, gas lighting, and gas meters.

It’s a brilliant little museum which explained how coal gas was produced; I’m not proud of the fact that I had no idea where gas came from in the old days. There is one dinky gasholder left, the second having been dismantled, but the various parts of the works remain.

Like many towns and cities, Fakenham Gasworks had its own showroom with the latest gas ovens and fires and kitchen appliances. On a different scale in terms of size and modernity, was the Hornsey Gas Company showroom which was built in the mid-1930s next to the Dutch Modernism/Hilversum-inspired Hornsey Town Hall (1935).

The building has a superb series of eight bas-reliefs (1937) by AJ Ayres on the exterior which illustrate the production and uses of coal gas (lighting, heating, cooking etc).

Gasworks and gasholders were for so long a remarkable if unremarked-upon part of urban life. But things are changing, and people like Russo, Chivers,

[Gasometer from a Train by Daniel Preece]

and artist Daniel Preece, are ‘collecting’ and celebrating gasholders.

And eagle-eyed compliers of film location websites are analysing cinematic backgrounds, and finding the King’s Cross gasholders in The Ladykillers (1955, above)

and Brentford Gasworks just visible in the riverside sequence with Ringo and a truanting boy in A Hard Day’s Night (1964).

[Bethnal Green]

Later this month, we are going for a walk along the Hackney section of the Regent’s Canal and will stop for some Guinness bread at Cafe Cecilia so that I can sit and gaze across at the immense, majestic Bethnal Green gasholders (larger 1889/9, smaller 1866) before they, too, are turned into something else - two huge, round, heated, outdoor swimming pools, if I had my way.

Happy Sunday!

PS thank you for all the lovely messages here and on Instagram about our beautiful new grandson - he’s doing very well and has already enjoyed listening to John Lennon

I think a gasholder would make an excellent place for a big trampoline.

Your cyanotype photo is gorgeous. Loved reading this!