unintended consequences

I plan to go back to the Tirzah Garwood exhibition at Dulwich because it has made such an impression on me.

For most people, Tirzah, who married the now very famous Eric Ravilious in 1930, is probably an unknown artist, so it makes you wonder if this amazing show would ever have happened if Persephone Books hadn’t printed her autobiography Long Live Great Bardfield. In this case, the law of unintended consequences came good.

[‘House at Great Bardfield’ (1945) with leaf prints and collage]

The incredible thing about Tirzah Garwood (1908-51) that emerges forcefully and joyfully in both the book and her work is just how much she did in the home: she was the epitome of a domestic artist but taking it to new levels. She was incredibly talented with a huge range of skills and interests, and was excellent at every creative pursuit she experimented with: wood engravings, models, embroidery, paintings, paper patterns, marbled papers, patchwork, collage, leaf printing, drawing, dressmaking, soft furnishings and, of course, writing.

[‘Vegetable Garden’ c1933]

So I found that the show offered/suggested a different way of going to an exhibition. Instead of going to admire work which has been selected according to specific criteria, this time it was to see a whole body of work - produced at home. It was fascinating to see what one woman could create while also catering/skivvying for Ravilious and Bawden, bringing up three children, and dealing with money woes, house moves, and marital issues.

If they are not simply unaware of her, critics have tended to be just a tiny bit patronising (“charming” is a word I’ve seen), or they have - I think - misunderstood her. It’s all too easy to see her as Eric Ravilious’ pupil then wife then widow, her early promise fulfilled more in her relationships than her art. But the exhibition makes absolutely clear that she was in fact a lot more than a wife, mother, friend, marbler and domestic dabbler.

[one of Tirzah’s marbled papers which she made with Charlotte Bawden]

And it’s even more about how, her success with marbled papers apart, no-one took any notice while she was doing what she did. It makes you wonder how many other artists, especially female artists, have been missed and unacknowledged because everyone was looking elsewhere and in the wrong direction. And it’s not as though Tirzah was creating and painting in isolation - she was surrounded by brilliant (male) artists in Great Bardfield.

I think many women in particular will go to the Dulwich exhibition and be astounded by Tirzah’s home-based output, and won’t be bothered by the range and the lack of focus on one discipline or medium. It’s her powerful creativity, her vision which mixes humour and darkness, surrealism and domesticity that are so amazing. Her body of work was broken up after her death, and is mostly in private hands now, but seeing it in one place makes you think how brilliant an exhibition in Brick House or a modern open studios event would have been.

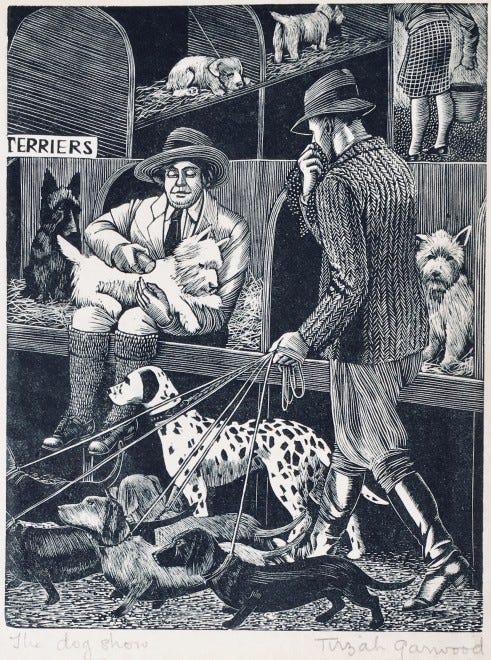

[‘The Dog Show’ (exh 19290]

In many of the works themselves there’s an accretion of small marks and lines which create texture, pattern, depth. They are like her life; it’s not a grand sweep but a daily dedication to the repetition of small marks and lines and stitches. She is brilliant at this, but the results are often far from from cosy and reassuring.

[‘The Old Soldier’ (1947)]

And the artists with whom she shares similarities are all edgy, unsettling, and strange: Henri Rousseau, Joseph Cornell, Leonora Carrington, and Victorian illustrators of children’s stories. This aspect of her work caused an unintended consequence for me personally: I hadn’t anticipated my reactions, let alone the sense of recognition.

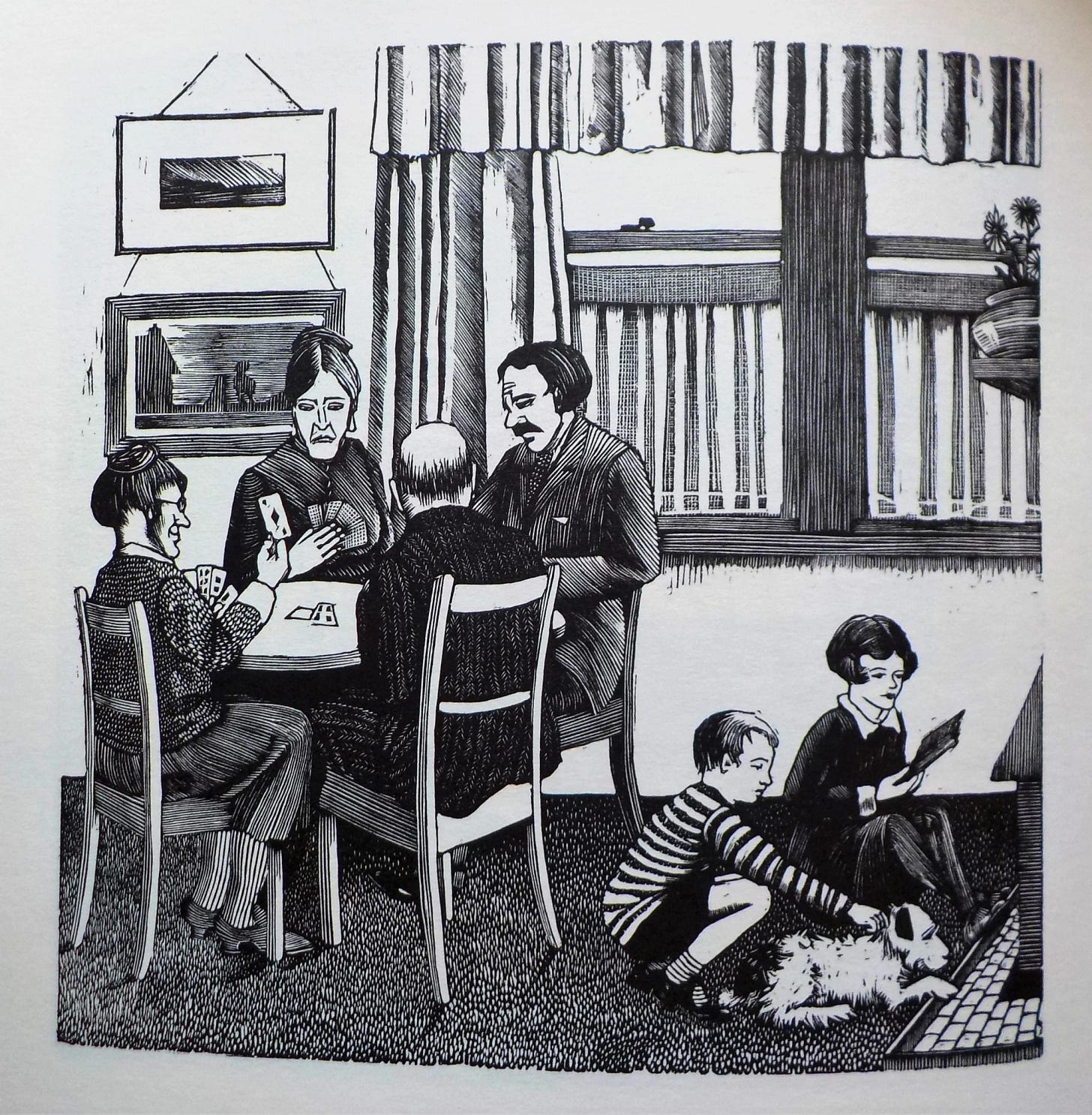

[1927]

This is Tirzah and her brother, and some scary-looking adults. The children appear downcast - the dog, too - and take refuge in companionship, a fire, and a book. The square-jawed woman is the wooden-tailed mother of my childhood nightmares.

At home, when I was little, we had a copy of Little Wide Awake (1967), an anthology of pieces from Little Wide Awake: An Illustrated Magazine for Good Children (c1870s) and I spent a lot of time with it, unable to put it down, absolutely terrifying myself. It’s very Tirzah in many ways. The story I returned to over and over was ‘The New Mother’ (1882) by Lucy Clifford. It’s about two children called Turkey and Blue-Eyes (even the children’s names are horrible) who are warned that if they are not good, their mother will be replaced with a new mother with glass eyes and a wooden tail. They aren’t and she is. I was so frightened by this, and although I knew glass eyes and a wooden tail weren’t likely, I was terrified my Mum might leave if we weren’t good. Let’s be honest, she didn’t always reassure me on this point - she once asked me, with absolutely no hint of a wink, to post a letter saying it was to an adoption agency and I cried all the way to the post-box, discussing with my loyal friend Janet whether or not I should post it. I was a good girl so I did. And did not appreciate the joke when I got home.

In 2011, Alan Garner wrote a new version of the story saying, “We need to be scared. It is healthy and good for us”. Not if life has already scared you as a child, it’s not. Reading her autobiography, you encounter a fear of adults (her predatory father in particular) that underpins Tirzah’s creative work; there is often a fairy-tale danger, a strangeness, and there is nearly always something unheimlich, uncanny, unsettling even about das Heim, the home itself. It is there in her later work with its mix of child’s-eye points of view, dolls’ houses, toys, miniature worlds surrounded by threats, darkness, woods, trees, poisonous plants, and often peopled by grotesque adults and even distortions of herself.

When I was seven, my father and my maternal grandmother (to whom I was very close) died within four months of each other, and my Mum gave birth to twins two weeks after her mother died. In less than half a year, we went from being the classic nuclear family of two parents, two children, one-and-a-half salaries, to a single parent, four children, one primary school teacher’s salary, no living grandparents, no death in service benefit, and the ever-present terror of us becoming orphans - because if death can strike twice in a matter of months, there’s nothing to say it can’t strike again. This fear hovered in the background until I was eighteen and could be the legal guardian of my younger siblings. Privately, I hoped it wouldn’t happen during O levels and then A levels or prevent me going to university. This is why Mary Portas’ story resonates so much: her mother died when she was a teenager, her father abandoned the family, and she had to turn down a place at RADA to look after her brother.

[Tirzah with John, James and Anne, 1940]

It is also, for me, what creates the undercurrent of sadness in Tirzah’s book; it really did happen to her three children and she knew it was going to. It was a scary fairy tale come to life, but not a Disney version.

[Villa at Walton-on-the-Naze (1948), leaf print, paper collage, box frame]

So, from an early age, I escaped by working hard at school and retreated into making things at home, because this was a sanctuary, a way of controlling my own little world. I created a whole troll universe in the bottom drawer of a dressing table. It had to be opened very carefully so as not to make all the cardboard furniture topple over or the pictures fall off the ‘walls’. I would have adored Tirzah’s series of houses and their imaginative domestic possibilities.

[Forthlin Road, 1962, photo by Mike McCartney]

As I got older, I tried all sorts of crafts in my bedroom - tie-dyeing, candle-making, gold-sprayed pasta collages, macramé, suede belts with 70s tassels, dressmaking, stuffed toys, knitting when I at last mastered it at the third attempt - while listening to The Beatles’ Red Album and Imagine. (John Lennon, now there’s someone who was permanently haunted and scarred by the death of his mother when he was seventeen, her second abandonment of him - yet Paul McCartney had a different personality and family altogether and coped better with the death of his mother when he was fourteen). I was a sort of low-grade, amateur version of Tirzah and, when making and reading and listening, I was totally absorbed and free from anxiety.

I know what I do still doesn’t fit into a single category, just like Tirzah, just like so many people. We are still hidebound by labels and categories and wanting/needing people to fit in. So it was an absolute joy to see an exhibition where these ideas are discarded and one woman’s work can appear in a wide range of media.

Normally I end a newsletter on a high note but, as I said, the exhibition had unintended consequences.

[‘Background to Toy Train’ (1950)]

This was made in 1950, the year before Tirzah died from breast cancer. To me it resembles an old-fashioned hearse waiting to take someone from their home with three children waving goodbye. It is unbearably sad and knowing.

No, I’ve changed my mind. We are going to end on a high note:

[‘The Four Seasons: Summer’ (1927)]

Happy Sunday!

I love reading your pieces each week and find them informative and fascinating but this week is so personal I thought I had to comment and say how beautifully it is written. It must have been hard to write something so personal. The exhibition of Tirzah’s work sounds amazing and I’m glad she’s getting the recognition she deserves at last.

. You touched a very tender spot for me too. Both my parents died before I was 12 and the photo of Tirzah and her children filled my eyes. I too filled my days as a child with sewing and drawing and making. Her son John took wonderful photos of lost Devon folk, particularly Olive Bennett and her Red Devon Cows. Have a look! And thank you!