solidarity

I had plenty of ideas for this week’s newsletter whirling around in my brain, but they all kept getting edged out by the overriding anxiety and horror about what’s going on in the world. There are times when even the new Bridget Jones film - preposterous in many ways, enjoyable for the duration, all falls apart under scrutiny except for Hugh Grant, prime scene-stealer - some new sock-knitting, a few rock buns, and several bunches of bright daffodils cannot dispel the daily feed of appalling news and, goodness knows, I now limit this very carefully.

Because Ukraine feels personal.

[Voronezh, 1960s]

I had a disaster of a year abroad when I was at university studying Russian and French. I won a prestigious British Council scholarship to spend ten months in Voronezh, 300+ miles south of Moscow, and at the last minute I turned it down. I just couldn’t do it. Unfortunately, this U-turn meant that I’d long missed the application deadline to be an assistante in a school which is really all I’d wanted to do. Very belatedly and in a mess, I went to Grenoble University but ended up being hospitalised with pleurisy and having to fly home. When I did return to France, I was utterly lost amongst the 38,000 students who’d already begun their courses and made friends, so I spent quite a few months pretending I was at the university but in fact never going inside a lecture theatre after backing out of the first lonely attempt and spending much of my time in Bristol, hoping no-one from the Modern Languages department spotted me. I look back now and think of course they must have known, but I was already in disgrace, they did nothing, and I floundered badly.

[Khreshchatyk, Kyiv (1979) - I walked along this chestnut-tree lined street so many times]

There were two positives to come out of this. The first was that it taught me how to take, and live with, very difficult decisions in the face of huge pressure from others who think they know what’s good for you. And the second was that with the money I got back from my insurance (lost luggage, ambulances etc) I was able to join a study tour and spend ten wonderful weeks in Ukraine with a group of British students who knew how to have a good time.

[‘Kyiv. Lilac Blossoming in the Botanical Garden’ (1984) by Volodymyr Sydoruk]

We went at the beginning of May when it was still cold, but by the end of May it was sunny and warm, the lilac was in bloom and the silver birches were in leaf, and it was just like a Tolstoy story.

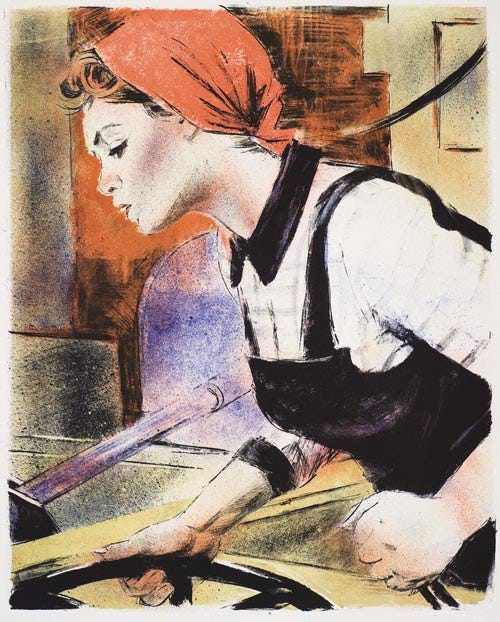

‘[They Write About Us: A Team of Builders’ (1969) by NP Karachaskov]

It was my first visit to the USSR; I’d started learning Russian when I was fourteen but didn’t get to the Soviet Union until I was twenty-one.

[Female crane operator, 1963]

One of the very first words we learned at school in text books printed in the USSR was крановщица or ‘lady crane-driver’. It blew my mind that this word existed (not so much that women could drive cranes), that it was possible to differentiate between male and female operators, and that the thinking behind it - gender equality - was enshrined in the language. (The French have been way behind in feminising occupations, with the lingering inbuilt assumption that professional jobs are done by men.) It’s all very well learning in principle how a language shapes thinking, but to actually be there and tune into a such a different way of communication and expression on a daily basis was a revelation (and hard work). I remember my first trolleybus journey along what was Gorky Street when we first arrived in Moscow and being utterly amazed that people could speak Russian fluently. Then we got to Kyiv and I thought I’d lost everything I’d ever learned until I realised with relief that people were speaking Ukrainian, not Russian.

We then had six weeks of Russian language lessons there at the Pedagogical Institute of Kiev (as it then was) followed by four weeks travelling around Ukraine to places such as Kherson, Zaporizhzhia, Kharkiv and Odesa.

[‘A Collective Farm Holiday’ (1937) by Sergei Gerasimov]

We visited sanatoria and renal clinics, schools, collective farms, tractor factories. We saw countless statues of Lenin and eternal flames,

[trolleybus in Kharkhiv, 1980]

we travelled on trams with women workers who wore summer dresses made from exuberantly floral cottons (still one of my major quilt inspirations), lounged on Black Sea beaches where many locals stood up to sunbathe (“because they are not tired after building Communism”, we were told), went to the opera for 30p a ticket,

[Potemkin Steps, Odesa, early C20]

reached the summit of the Potemkin Steps, ate dark rye bread, sour pickled cucumbers, ripe juicy cherries and

delicious Plombir ‘milky’ ice cream.

[carbonated water vending machine, 1959]

We drank milk and carbonated water from vending machines using the same glass or couple of glasses that everyone else did, and were welcomed with bread and salt and speeches everywhere we went.

Of course there were all negatives that went with the USSR and Communism, from public toilets with no doors to the same soup with fish bones and globules of fat floating on the surface reheated day after day in the hostel, shortages and queues, and strict limitations on what we could do. And the ever-present fact that people there had no personal freedoms; we had a tutor who spoke beautiful English and was extremely well-read and yet he would never have been allowed to travel to the UK, and to this today I cannot bear the idea of people’s rights and freedoms being controlled and restricted by others purely for political/vindictive reasons. Yet, despite the fact that we were in a country which had been annexed by another power, I was so curious, so eager to learn, that it was one of the best times of my life and, amazingly, Ukraine brought me back to myself.

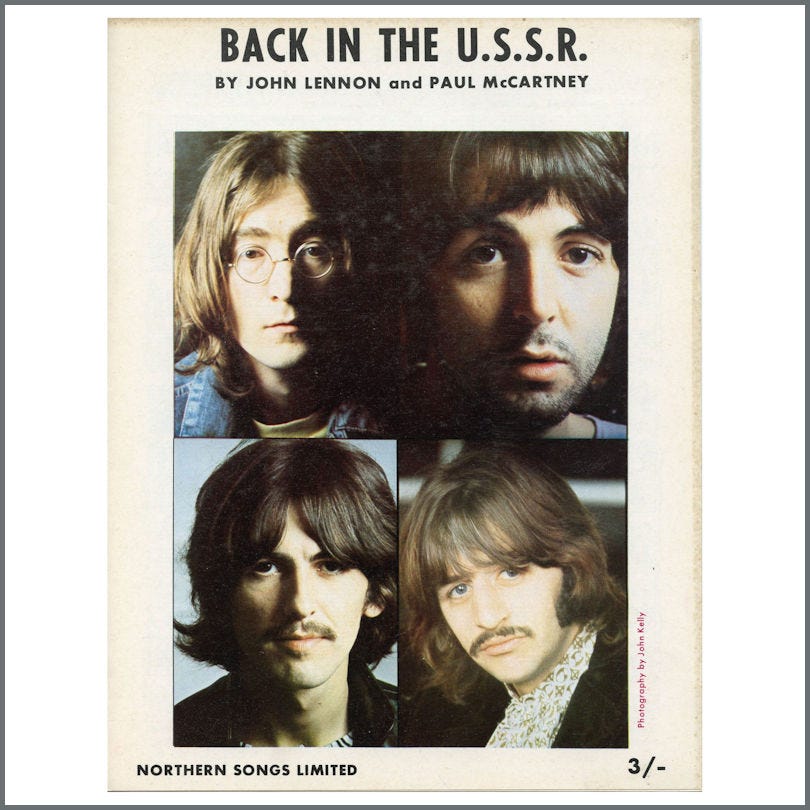

[soundtrack to revision for many a Russian vocab test, 1968 sheet music]

When the war began in 2022, I was taken back to the USSR (“the Ukraine girls really knock you out”) and was reminded of all the places I’d visited - now with their Ukrainian names restored - many of which have been in the news constantly ever since for terrible reasons. It was bad enough when Russia was the aggressor, but in all my years of studying Russian and Soviet history and politics, I would never, ever have imagined that the US would align itself with Moscow. These days I sound like a record that’s stuck, constantly wailing “why?”. I don’t even want the answer, it’s too banal and terrifying.

I know that Ukraine at the height of Soviet Communism might seem like the last place you’d regain your sense of who you are, but funny things happen in life. And my solidarity with this country, its people, and with Volodymyr Zelenskyy is as strong as ever.

Happy Sunday and Слава Україні!

PS these are not my photos, not sure if I even came back with any, but it’s all as vivid as ever in my memory

I really appreciated this deeply personal account. At around the same time you were abroad as a student , I was doing my year abroad in America . If my 20 year old self knew that there would be a day when the American Leadership would align itself with Russia , I’m not sure I would have believed it. Much as my 60 year old self found it hard to believe the appalling, bullying, ill informed and vile behaviour televised from the Oval office. I dread to think what we will wake up to next and so, like many of us I suspect, I try to stay informed whilst finding pleasure in the things under my influence and control…. Like a Sunday morning cuppa while reading your substack for the week. Thank you, as always, Jane.

Thank you as always. I am sure you know (or maybe not?) that the vast majority of Americans are as appalled as you are and are trying to figure out how to stop this terrifying train wreck. None of us ever expected to be so ashamed of being American.