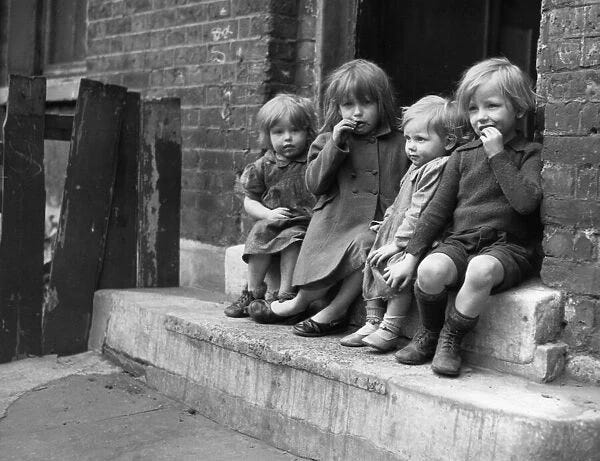

[Doris Street, London, 1943]

I have some very happy memories associated with doorsteps. I loved sitting on my Nana’s front doorstep eating bacon butties with the little girl from next door, queens of all we surveyed: red-hot pokers, Fairey’s aviation factory, Cringle Fields (it’s no wonder I enjoy words and names). This was the same doorstep from which my Mum had watched bombs falling on Manchester when she should have been in the shelter.

[Near Upper Brook Street Manchester, 1964, Shirley Baker]

The doorstep is an unusual place, a transitional space. It’s neither in nor out, it’s safe but on the edge, public but also domestic, semi-private and semi-public, and provides a degree of openness and a degree of protection. The unwritten social rules in the road we grew up on meant that, for an unscheduled social meeting or to request a favour or to borrow something, one person stood on their doorstep and the other stood lower down. You didn’t go further in and the other person didn’t come out; many times my brother and I stood behind Mum while she chatted endlessly with our neighbour Mrs Crawley with her son our friend behind her, the three of us laughing and rolling our eyes at our mothers’ behaviour and weird rules.

I am still fascinated by the ways in which doorsteps are used, their importance, their role in the life of a street. They always make me think of the brilliant Jane Jacobs and her theory of ‘eyes on the street’; doorsteps and stoops are important places from which to watch the ‘intricate ballet’ of movement and interactions which contribute to the well-being of a street, and making it a good place to live.

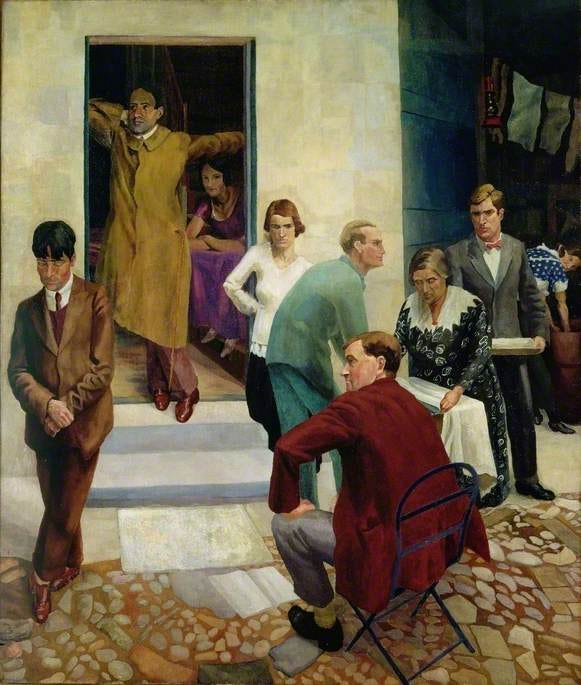

Unlike my old road, Gathering on the Terrace at 47 Downshire Hill, Hampstead, London (c1924) by Richard Carline does not contain a lot of laughs (nice washing line in the shadows, though) with Stanley Spencer looking shifty on the left, but it does beg the question why this is happening on the doorstep? It is nicely emblematic, though, of the way in which gossip, local information, news, sugar, milk can all be exchanged on the doorstep. When I had to make a decision about which language option to take at school, I vividly recall the doorstep discussion my Mum had with Mrs Crawley (see above/Russian) with all the kids running around as my future was deliberated in the road.

[the McCartney family on the doorstep of 20, Forthlin Road]

During the pandemic the doorstep suddenly became highly significant, the limit of our public lives during lockdowns, with other people not allowed over the threshold. There was a lot of talking/shouting to friends, neighbours, and family, from a position of doorstep safety while they stood at the end of the path, on the pavement, at an unnatural distance. We stood on our doorsteps to applaud the NHS, to receive deliveries once the delivery person had taken the requisite number of steps back, to talk to someone outside our bubble for a moment or two. Families had their photos taken on doorsteps; some professional photographers such as Anna Hardy offered (and still does) “doorstep portraits” and others like Tom Soper turned lockdown shoots into a project which would “form a small, interesting archive of this incredibly unusual time”.

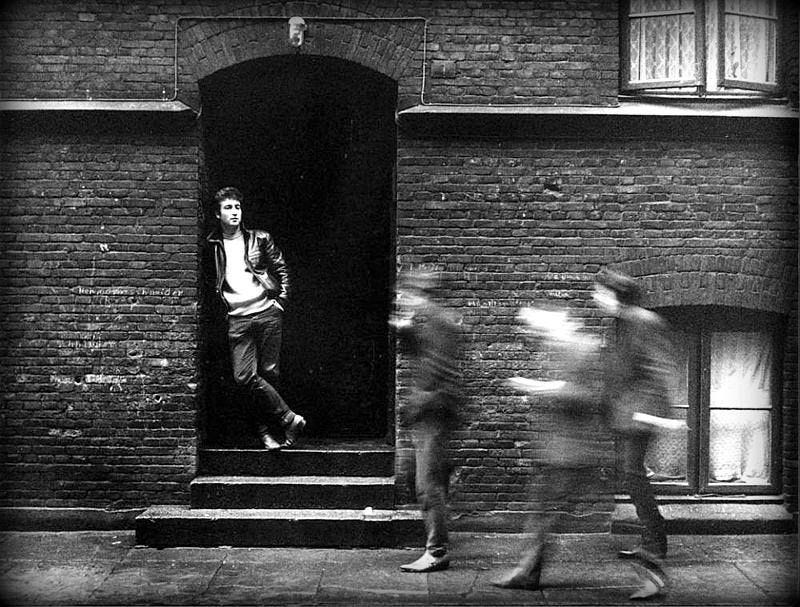

[John Lennon (1961), Jürgen Vollmer]

There are plenty of well-known media doorstep moments such as the classic Cherie Blair photo taken the morning after the Labour landslide in 1997 or when the paparzzi stalk Anna/Julia Roberts outside the blue door in Notting Hill, but instead get Spike/Rhys Ifans posing on the doorstep in his grotty grey underpants. A doorway and step provide a perfect frame, especially in black and white portraits; my favourite is John Lennon in Hamburg, standing on the step in the doorway like a saint or statue in a niche. He’s tough, confident, nonchalant, but also the boy-next-door.

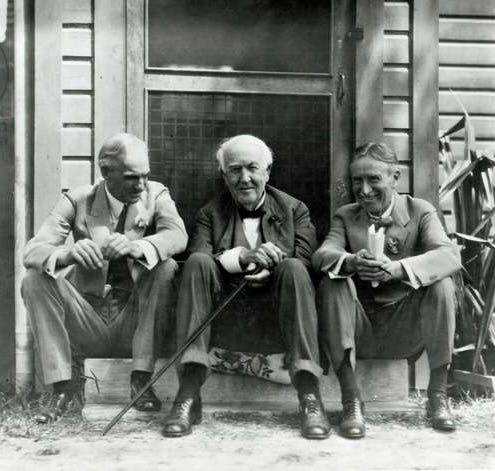

[Henry Ford, Thomas Edison and Harvey Firestone (1931)]

Squishing people together on a doorstep even makes mega-rich industrialists look like relaxed, genial, ordinary men of the people.

Then we have the things that are left on doorsteps. This past week it’s been pumpkins, but it can be milk bottles, newspapers, fruit and veg, excess allotment runner beans and courgettes, parcels, babies. When my late brother was having chemo during the pandemic and couldn’t go out or see anyone, his friends would leave sausages or his favourite ice cream on the doorstep, drive away, and phone to let him know. “Hey, Matty, I’ve left some chipolatas on your doorstep.” Just lovely and funny and heartbreaking.

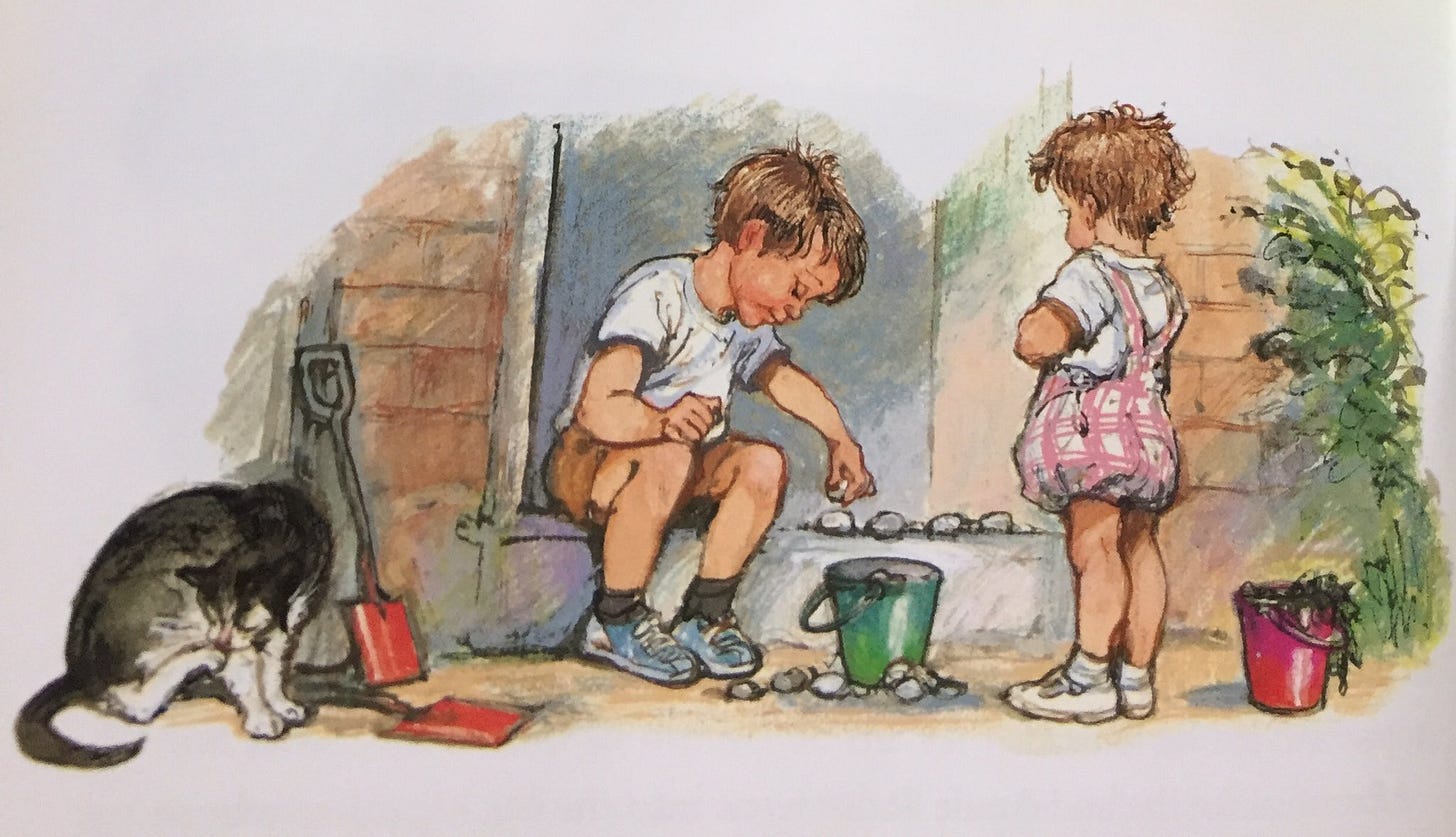

[illustration from ‘Bonting’ by Shirley Hughes]

And what can you do on a doorstep? Step out in your dressing-gown to check the weather, pretending if seen that you were doing something far more important, pod peas, play jacks, read a book, arrange stones and pebbles, collect the milk and/or newspaper (in the olden days), drink tea, eat bacon butties, watch the world go by, feel the sun on your face.

[Park Hill, 1961, Roger Mayne]

One of the interesting things about the pulling down of so many inner-city terraced houses with doorsteps and their replacement with high-rise flats is just how important the doorstep still was, as a social location and a symbol of coming home. Even the flats on the “streets in the sky” of the infamous, brutalist Park Hill flats in Sheffield had doorsteps to recreate street-level life, but sadly most entrances to 1960s flats were reduced to a doormat. I recently watched Terence Davies’ Of Time and The City (2008) and was struck by the way it showed Liverpool streets and doorsteps in the 1950s and 1960s and the life which took place there, all included with a mix of clear-eyed awareness of poverty and a big dash of sentimentality. But he captures all the reasons why these terraces should never have been demolished in the first place.

[Laugharne Wales by Brian Seed]

A lot of the people in the film would have been proud of keeping their doorstep clean, swept, and polished as a way of making visible a welcome as well as their standards of housekeeping and respectability.

[A shopkeeper washing her doorstep, Benwell, Newcastle (1963) Colin Jones]

Of course, the doorstep has its own negative aspects. Scrubbing, ‘stoning’, and polishing are dirty jobs, hard on the hands and knees. And there are the doorstep intrusions which may or may not be welcome, but which can almost constitute an invasion of privacy, such as door-to-door salesmen, canvassers, charity collectors, not to mention appalling journalists who think it’s fine to ‘doorstep’ someone. Although the old custom of Friday evening collection of milk payments or insurance subs did have its lighter side when my little twin brother and sister went through a phase of asking every man who stood on the doorstep, “will you be our daddy?”

I have never forgotten Doris Lessing’s reaction to being told she’d won the Nobel Prize (2007) by journalists waiting outside her house for her to return from shopping. “Oh, Christ”, she said when they told her, and plonked herself down on the doorstep. The photographers got their picture of an old lady, her dignity somewhat compromised by the ordinariness of the shopping bags and location, I feel, and not given the respect due to someone who has just won a Nobel prize.

Too often now, though, “on your doorstep” is a metaphor, not a physical reality. It’s interesting that I can find nothing written on the social life of the doorstep, the importance in street life of that step to sit or stand on, of the little platform or vantage point from which to view the theatre of street, its significance as a launch pad to the outside world. It’s never too late to treasure the doorstep.

Happy Sunday!

Love this piece on doorsteps with all of the wonderful pictures. I am lucky enough to have both a front and a side doorstep. The front step is almost entirely devoted to potted plants, sunbathing cats and an occasional splash of pumpkins and Christmas lights. The sidestep provides me with the perfect upper perch to speak to whomever has arrived at ground level. There is a storm door for added protection from the less respectful visitor. How people act at the doorstep reveals so much about who they are!

I'm now in my 70s and well remember my father painting the doorstep of our brand new council house with cardinal red paint. My mum would then polish it every week with special red polish. Absolutely lethal really as it was very slippy but it showed the world what a good housekeeper my mum was. My mum lived in that house for nearly 60 years and as she aged the step became neglected and the paint flaked away. A new family live there now. I wonder if they've cleaned off the old paint that was left and query why it was ever painted.