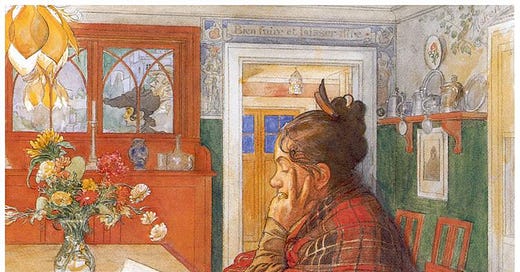

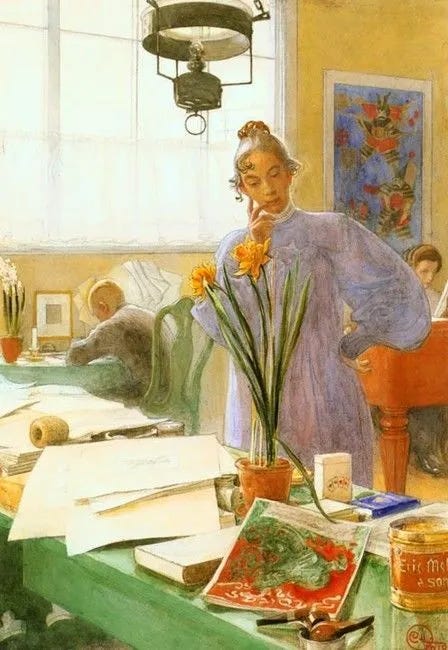

[Karin is Reading (1904)]

The case of Karin Larsson (1859-1928) is a fascinating one.

[Now]

She is so very present in Lilla Hytnnäs, the house she shared with Carl and their family.

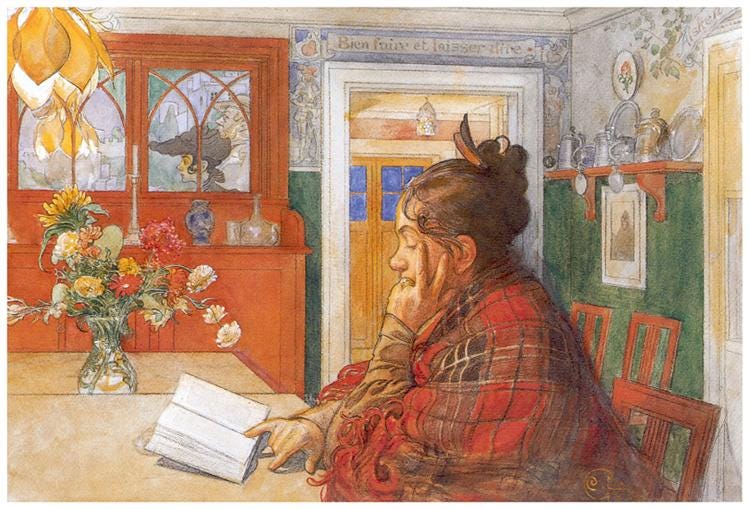

[Then: Sunday Rest (1900)]

She is in many of her husband’s paintings, her colourful, innovative textiles and the material traces of her life there are everywhere, her face is on a door, and there are beautifully lettered inscriptions dedicated to her on the walls.

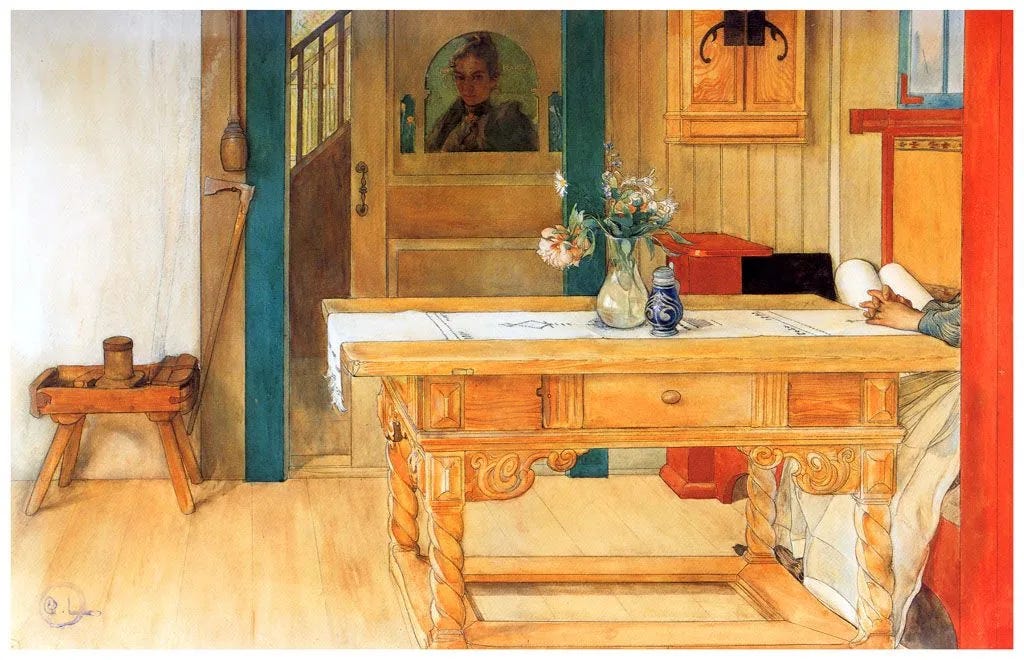

[The Workshop (1910). Karin’s creative space, shared as always with the family; she is at the loom, and one of her modern pieces can be seen]

She was Carl’s collaborator, ran the house, cared for seven children, oversaw extensions, building and alterations (often when he was away for long periods), and he always sought her approval before sending out his work. She designed modern, loose, comfortable clothes for herself and the children, grew flowers and vegetables, stitched, embroidered, and created exceptional domestic spaces.

[Getting Ready for a Game (1901)]

Yet very little is known about her.* It’s hard to work out if this was deliberate on her part or because of Carl’s enormous fame (and his frequent failure to acknowledge her contribution). What is known is that Carl did not think women should be artists, and that they should instead be the angels of the house.

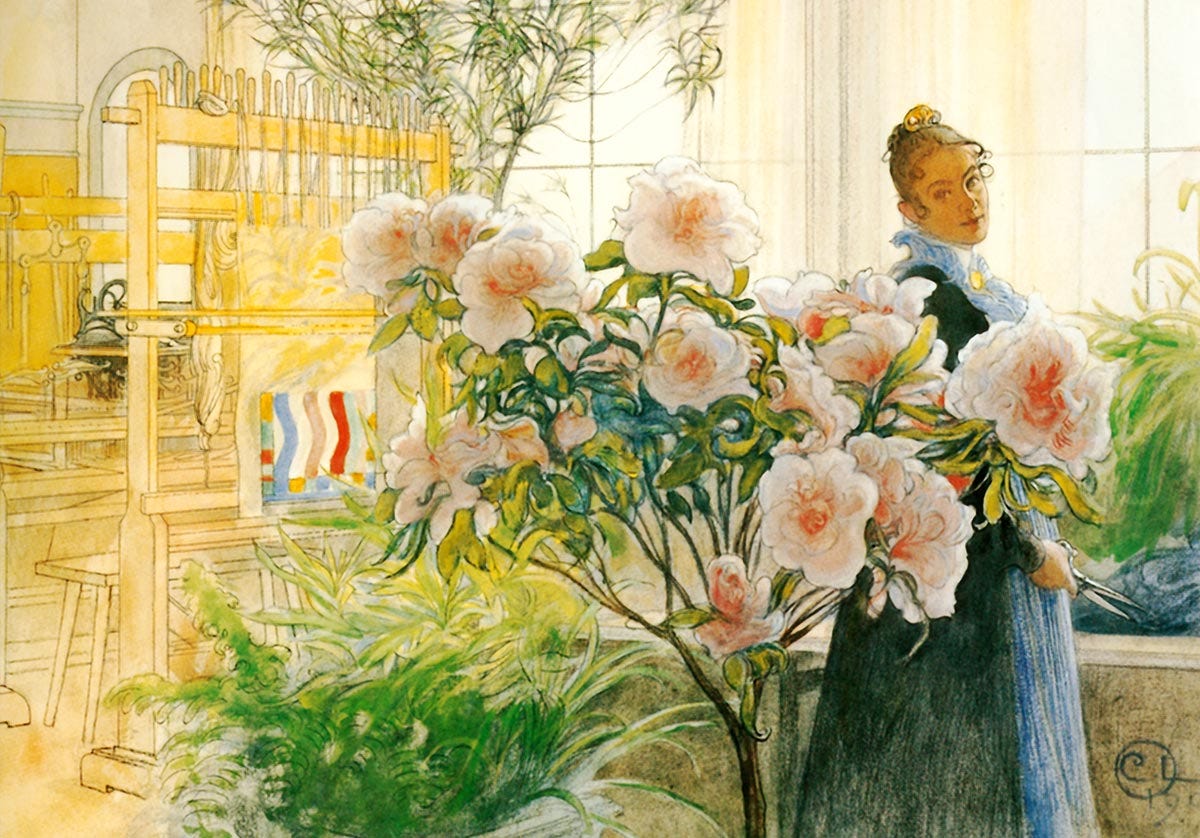

[Azalea (1906)]

While the man has let himself down on this score (and I’m not even going to start justifying it by saying this is how it was at the time etc), I do wonder if it truly held Karin back. Because, despite training as a painter, the home and domestic life they shared became a huge and vital source of inspiration for her creative interests.

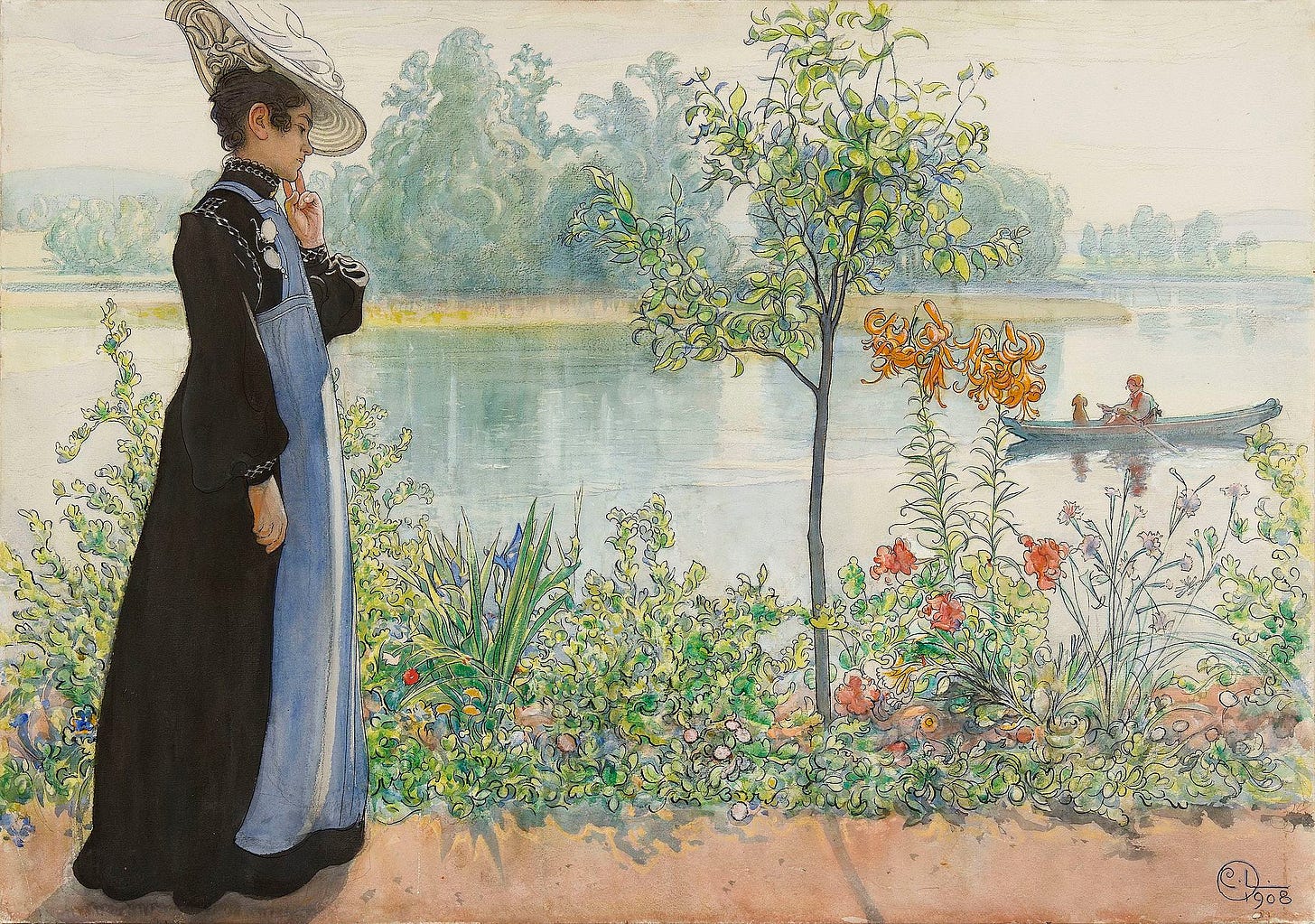

It was an apparently enviable life. In all the images, Karin exudes calmness, whether she is reading, working on textiles, at her loom, dealing with children, dinners, and celebrations. With her ever-youthful face (even in older age), her funny bobble-and-tendrils hair-style, her long, patterned 1970s Laura Ashley style dresses she has a sweetness but also appears graceful, spontaneous, natural and, I’d like to think, always herself. She may have been the angel of the house but she was not the tightly corseted, Gothic-meets-John Ruskin-ideal type.

Instead, she is the personification of a very gentle style of domesticity.

Clearly, everyday real life could not always have been as it appears in Carl’s paintings as it’s an edited version. He chooses what to show and include, and captures very specific moments; who knows, in the next moment it could have all gone noisily argumentative and chaotic. Even with this level of editing, it is - gratifyingly - imperfect; knitting could be left on a table, something which was not allowed by Jim Ede in Kettle’s Yard. Unlike that of Helen Ede, Karin’s presence has not been erased from the house. Far from it.

[the dining room, Karin’s family tree embroidery]

Karin may have given up her painting but as the V&A exhibition catalogue says, there is no proof that she missed it. Today we might wonder if this led her to feel stifled or constrained, but maybe we are making modern assumptions. It’s also perfectly possible that her partnership with Carl gave her the opportunity to break social and homemaking ‘rules’, develop her own textile techniques, design the furniture she wanted to use, create beautiful rooms, combine being unconventional with traditional roles and her own version of the angel of the house.

It has always been difficult to separate out Karin from Carl, but that was no excuse for her contribution being neglected for so long. It wasn’t until the joint exhibition at the V&A in 1997 that that her life and work were even recognised and researched.

[Karin at the shore, (1908)]

So it was rather disappointing to visit the temporary summer exhibition in Sundborn which focusses on Karin. All this incredible creativity and yet it was almost impossible to get a sense of her personality and individuality. It was mostly reproductions and replicas of her work*, the odd sewing machine, and some remakes of her dresses.

But. Maybe this is what Karin wanted. Maybe she found fulfilment in her lifetime and didn’t seek greater or wider recognition or an afterlife for her work. Maybe, instead, it is the spirit of Karin, her clear delight in domesticity, and her vision of a beautiful, comfortable, happy home, that should be celebrated.Maybe the clear communication of her enjoyment of place, pattern, colour, sewing, weaving, tapestry, flowers, reading, seasons, celebrations, and, of course family life is her greatest legacy, especially now, when domesticity has become so entangled and confused with the complex politics of feminism.

Karin wasn’t expecting conservators to be examining (and judging) the textiles she made solely for her home, poring over her untidy stitching, tut-tutting at the loose ends and messiness of the backs. She wasn’t fussy about dyes, whether they were aniline or vegetable (disappointing many people today who judge her on criteria she herself would never have applied to her work) as she just used what she could find. She definitely didn’t intend for her house to become a museum; for her, a home was a living thing, and she wanted her descendants to keep it alive which they do - by still living in parts of it.

[1913 etching]

Instead, she valued everyday life, unpretentious local craft skills and folk art, eating out of doors with children, nasturtiums, books, and cross-stitch. It seems to me perfectly possible that she achieved all she wanted to achieve. So when we go to the house we should perhaps be thinking of a version of Wren’s epitaph: ‘visitor: si monumentum requiris circumspice’. It’s just that, sadly, the inspirational monuments created by female domestic artists usually last only as long as they do. So it’s fortunate that Karin’s is still there to celebrate her wonderful domestic artistry.

Happy Sunday!

*it’s possible to buy kits to make Karin’s original designs

PS I’ve left out the biographical details, such as they are, but they can be found elsewhere. The V&A catalogue is useful on these (secondhand copies are on abebooks), and I’ve just bought Karin Larssons värld by Lena Rydin which may take me a few years to read/translate.

What an utterly fascinating woman! It appears to me that she put into practice Morris' suggestion to have nothing in one's house unless it was useful or beautiful. As I read your piece this morning, I thought about what her life might have felt like to her. She had space and support to be creative. She had freedom of movement and thought. And, to a great degree, she had freedom to make her life what she wanted. Those were all revolutionary and I would think she had such delight in those options. The angel in the house culture was so pervasive that it seems to me that she found the space to defy much of that suffocating culture. The fact that Larsson seems to draw his muse from the life she created indicates to me the power she held in the household. More than that, her creativity found an outlet in things that the family needed -- clothing, household textiles, furniture, and so on. I wonder, too, if perhaps her greatest legacy is not the tangible, but the intangible. What effects did her choices make on her children and those around her? The fact we are touched, intrigued, admiring, of her life suggests that her influence is still rippling .... not bad for a woman who appears to have not expected or sought appreciation for her creativity or life....

Very interesting, and I'm really conflicted about this. I'm not remotely an artist, so I don't know what it would be like to put aside a wellspring of creativity, even if it was redirected into other outlets. How much of it was unthinkingly conforming to the norms, and even then, did she have a pang of regret? I've been reading "Millions Like Us", by Virginia Nicholson, and have been struck by the relief with which many women gave up work after the war and went back to being housewives. I imagine if you were working in a munitions factory that would be easy to do, but if you had been breaking codes or translating French and German, wouldn't it have been hard? Whatever she felt, running 7 children and a labour-intensive home didn't deflect her from creating in the domestic sphere. One wonders how Carl would have coped with that!