Unusually for me, I’m going to reprise the subject I used on this week’s Persephone Post, because it’s given me much to think about and made me want to go further with it.

I’ve just read the recently published Interwar:British Architecture 1919-39 by Gavin Stamp (1948-2017), variously described as “majestic”, “erudite”, “illuminating”, “a superbly detailed picture of an architectural era”, and “the definitive history of British architecture between the Great War and the Blitz”.

[Shakespeare Memorial Theatre (1932) by Elisabeth Scott]

Now, I am fascinated by interwar architecture and look out for it all the time. I always wondered about the semi-detached white houses with bow windows that I saw from the top deck of the number 9 bus on my way to and from school,

[ABC Cinema (1938), as it then was, Ardwick, Manchester, 1963 - with Moderne curves and concrete]

as well as the huge white cinema in Ardwick which I passed on the 92 bus. For years, I’ve loved inter-war lidos, the vast art deco 1930s London factories in Slough and along Western Avenue in London, the 1930s schools which look like factories (and in a way were/are), plain interwar council housing, the fancy Odeon cinemas and the innovative churches which look like cinemas (and in a way were/are),

[St Nicholas, Burnage (1930-32), Grade II*, by NF Cachemaille-Day]

especially the one in Burnage which I really could not accept was a church when I was a teenager. (Also, have to admit I like the names of the famous interwar church architects: NF Cachemaille-Day, FX Verlade, Ninian Comper, Edward Maufe (né Muff) - was a wild name a prerequisite for the job?)

[9 Wilberforce Road, Cambridge (1937) by Dora Cosens]

I am also oddly drawn to the white houses with flat roofs and Crittall windows that you find in places like Frinton - and Cambridge - and are the embodiment of (often dubious) ideas about fresh air, sunshine, and hygiene, and so ill-suited to the British climate.

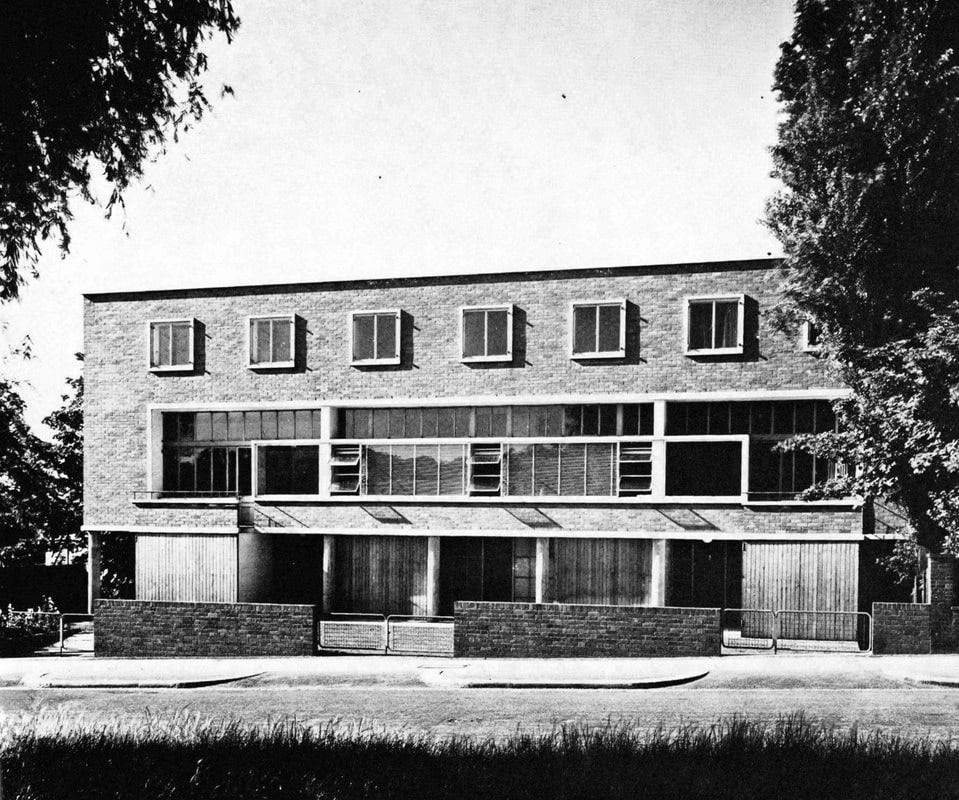

[Fawcett Building (1937), Newnham College, Cambridge, by Elisabeth Scott]

The brief interwar period was a brilliantly varied and experimental and exciting period. And at 520+ pages, Gavin Stamp’s book is, correspondingly, a whopper, crammed with buildings, materials, references, styles, critics, and in-fighting. And men. Lots of men. Enormous numbers of men. In fact, by the end of the book, I could have been led to believe that that in those twenty very active years, it was only men who designed, built, assessed, reviewed, defined tastes in, and argued about, architecture.

[Mary Crowley (later Medd, and the subject of a book) worked on Willow Road with Ernõ Goldfinger]

Stamp’s widow, Rosemary Hill, took over the arrangements for the posthumous publication of the manuscript when he died in 2017. In her introduction she mentions Ethel Charles, the first female member of RIBA in 1898 (and “her sister” - unnamed, but actually Bessie Charles who followed Ethel in 1900), and is at pains to claim that architecture was “among the more open-minded of the professions of the time”, even though it was “predominantly, a man’s world”. I get the context. But still. Where in the book are the women of this “open-minded” world?

Now I’m sure Gavin Stamp was a very nice man, a great architectural writer, academic, and journalist, probably great fun on visits or tours, a fine speaker at events and conferences. But, baffled and increasingly irritated, I started counting the references to women in his huge book. Eventually, and call me obsessive if you like, I did an analysis of the index which runs to 16 pages of three columns of small type. And there I found the names of 755 men (give or take a few), and 28 women. Included in the twenty-eight are two contemporary architects, one architecture student, Ethel Charles (abandoned after the introduction), and a light mix of film stars, aristocrats, widows, writers, and clients, plus a designer, a housing consultant, a sculptor, and one bona fide queen. And in the hundreds and hundreds of buildings included in the text there is one, ONE, ONE!, building designed by a woman: the Shakespeare Memorial Theatre in Stratford-upon-Avon by Elisabeth Scott, and my goodness this has to do a lot of heavy lifting as they say in order to convince the reader of the so-called ‘open-mindedness’.

So, were there no female architects in the interwar period?

[Eleanor Hughes, centre, and Winifred Ryle, being congratulated by fellow AA students on their membership of RIBA in 1922]

Yes, indeed there were. And they were not just polite lady amateurs; they attended the same lectures, read the same books, saw the same buildings, took the same exams, won the same prizes as the men. As Elizabeth Darling, who compiled several female architects’ DNB entries, writes, it’s not that the buildings were not built or are not still here, it’s that they are not seen by so many people, which is incredible because you have the tangible, bricks and mortar physical evidence of someone’s work. To not see them amounts to wilful disregard and an unbalanced, misleading retelling of history.

Because it doesn’t take much effort to find the women. Elisabeth Scott, of course. Mary Crowley, later Mary Medd, the subject of a book. Margaret Justin Blanco-White. Elizabeth Benjamin. Norah Aiton and Betty Scott. Dora Cosens. Jessica Albery.

Gertrude Leverkus, who was appointed Women’s Pioneer Housing organisation’s architect in 1924 to oversee the conversion of converting large London houses into flats and bed-sits for women.

[King’s Knoll (1933, grade II listed), by Hilda Mason]

And Hilda Mason, whose reinforced concrete church in Felixstowe made huge waves and whose amazing house, King’s Knoll, in Woodbridge sold recently (it was listed at not-insignificant price of £2.5 million).

The fact that Interwar is not a solely gazetteer of completed buildings and their architects but an overview of many contemporary discussions, debates, and developments (eg the emergence of the first generation of qualified female architects) makes it even harder to accept the omissions. Many men who worked in roles related to, and associated with, architecture and building are included, but you really wouldn’t know what there were women also doing these jobs at the same time. As Lynne Walker, herself an architect, says, “the inter-war period was a golden age for women architects who flourished professionally and were well-received critically, but history has been less kind to their work and reputations, misattributing it and assigning it to their (male) partners, neglecting their concerns and values or ignoring them altogether”.

Ultimately, the book begs the question of how, now that so many organisations and people are making efforts to acknowledge and celebrate women’s contributions over the last 100 years to all sorts of spheres, not just architecture, when 31% of all architects are now women (not 0.31% or something), when 72.7% of all accepted offers to study architecture at Cambridge University in 2022 were to women, a book which is so male-centric in defiance of the historical and built reality can be published. If this is the “definitive history” of the period for today’s readers, heaven help us. Are we obliged to accept it as the best, most comprehensive survey of its kind? How does this reflect on publishers and editors who, while nowadays bending over backwards to be inclusive and sensitive and careful, manage to allow a whole cohort of female architects and their work to be airbrushed out of the biggest, newest account of the period? This, in contrast to the universities and professional organisations which are making solid efforts to acknowledge and highlight women’s contributions (here, here, here, here, here, and here).

It’s very clear that what’s needed is a big, fat book on women in the world of architecture, and that women are going to have to do it for themselves. This will not be easy. I know whereof I speak. Several years I ago, after the publication of my book on stained glass, I had a contract to write one on female stained glass designers and makers, of whom there are many (far, far more than you’d imagine) and whose work is gloriously large, colourful, permanent, and in plain sight. I worked on the research and writing for six months, then the publisher was acquired by a bigger publisher, and my book landed on the desk of an editor who wasn’t interested in offsetting the prevailing story of stained glass. The contract was cancelled and I got £500 compensation for my trouble (approx £83.33 per month). So the book on women’s enormous contribution to stained glass design did not see the light of day, and probably won’t any time soon.

It really is a case of needing to go back to the drawing board.

Happy Sunday!

Excellent newsletter and highlights precisely the problem over and over again with women's participation, in arts, media, science, medicine, its always the same: the women are there, often right from the start, but they get airbrushed and then erased from history by people like Gavin Stamp. It is the critics and the historians who vanish them and do them and future generations a wicked disservice. The current exhibition at Tate Britain of women artists called Now You See Us is a brilliant example of this and there is so much work to be done to bring the excellent work that so many women have done back into the light where it deserves to be. I try to do this with the ultimate female occupation - textiles - in the Haptic & Hue podcast - where the hands that fashioned textiles throughout history are simply anonymous and the stories rarely if ever told. Please please go back to writing the story of the women who made stained glass - they deserve the attention!

I’ve just forwarded this to my friend, whose great aunt was an architect in the 1930s. Her grandmother was a solicitor. In rural west Wales. They must have been formidable sisters.

Now You See Us is a fantastic exhibition. Although it made me ponder how many talents were lost under mountains of washing, unending pregnancies and a lack of access to any creative materials/tuition.