gathering stitches and thoughts

Or, put simply, smocking. (Sadly the usual titles of pieces about smocking are terrible puns, and that’s saying something as I love a good pun. ‘Smock value’. ‘Smock it to me’. ‘Smock of the new’. All just make me want to use my current favourites emoji: 🤦🏻♀️)

I say all this because the highlight of this week has been a visit to V&A East Storehouse. It opened at the end of May this year and has generated acres of articles about the brilliance of the design, and it is indeed unlike anything I’ve ever seen.

[Jo’s attic in ‘Little Women’, 2019]

It’s a proper storehouse, like different levels of an enormous attic in which stuff has accumulated over the years and in apparently random fashion. A Frankfurt kitchen, pub signs, mahogany furniture, clocks, David Bowie’s stage outfits, a section of the Smithsons’ Brutalist Robin Hood Gardens housing (on the left of the photo) all laid out in a glorious mix.

It’s just a few minutes’ walk from Hackney Wick Station (2018), itself a pretty amazing piece, a mix of art and architecture, glass and concrete, historical and contemporary references. (See The Beauty of Transport for more.) You walk over a bridge - or along the canal if, as I did, you exit the station in the wrong direction - and into what was the Olympic Park and is now a mass of new buildings. Including the V&A East which is as far from founder Henry Cole’s vision and original building as you can imagine. But form and function marry beautifully here.

It is possible for anybody, yes anybody, to order up to five objects to be brought out of storage for you to look at. For free. In a lovely airy study room. With nice staff on hand to help and advise. And nasty purple latex gloves so that you can actually handle them (where allowed). You make your selection - easier said than done because this is the V&A after all - book an appointment, fortify yourself with a cup of tea and an excellent pain au chocolat in the little cafe run by E5 Bakehouse, and get all excited when you see what look like five white body bags on a hanger holding your five C19 smocks.

I wanted to look at classic, traditional hand-made smocks made for and worn by agricultural and rural workers before the advent of rural depopulation and industrialisation, and machines which made wearing voluminous garments dangerous.

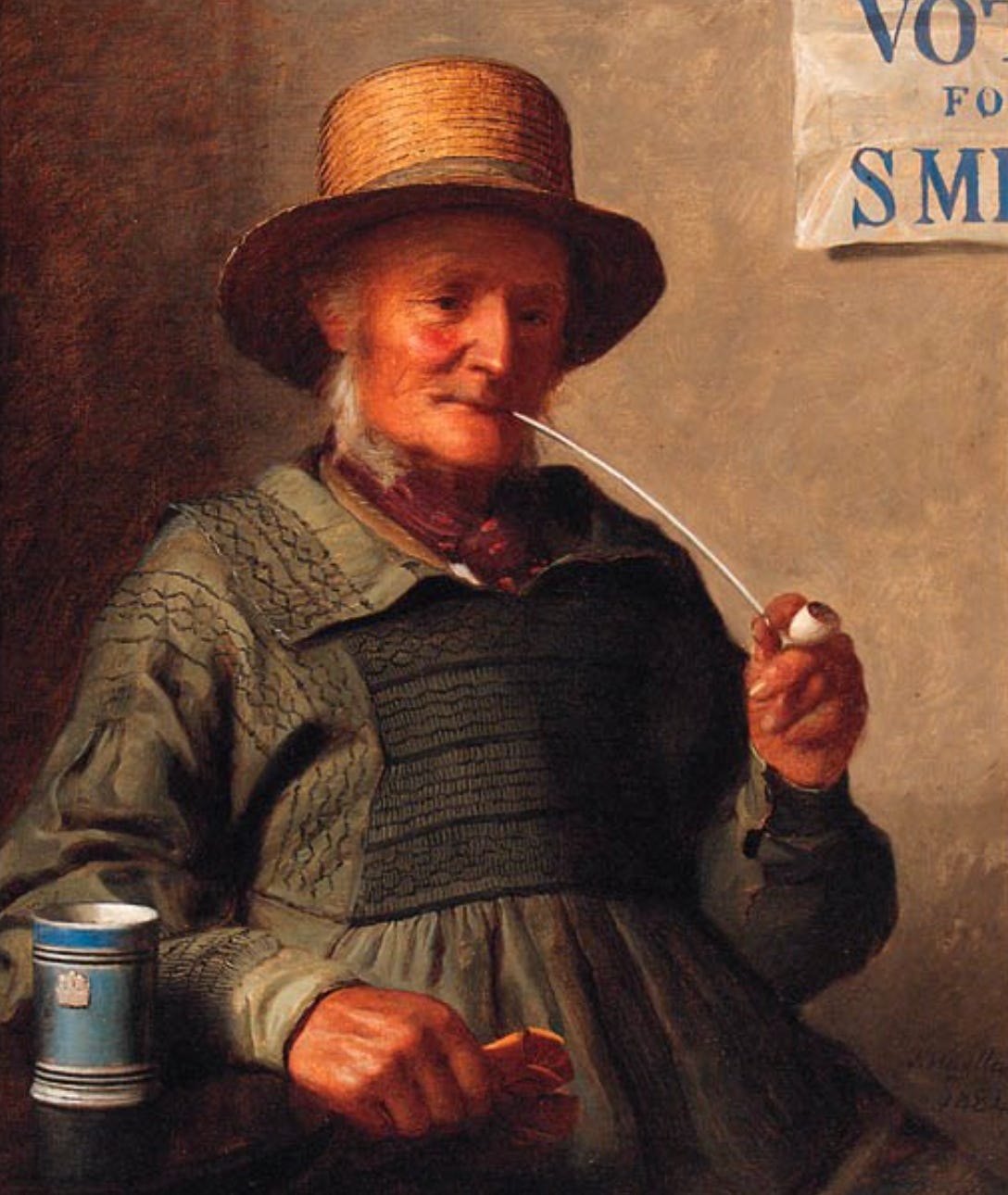

[‘More Bother Than It’s Worth’ (1884) by James Hayllar]

The kind of smocks mentioned in novels by George Eliot and Thomas Hardy, and frequently painted by James Hayllar. The lovely, elaborately smocked dresses for women and children which came later at the end of the C19 as the classic smock frock fell mostly into disuse except perhaps for special occasions, feasts and Christmas, could wait till another time.

So I ordered what I hoped would be a good range of smocks from early C19 to second half C19, simple to sophisticated, heavily worn to almost pristine. In the end, they kept me totally engrossed for two hours.

I wanted to look at their construction and the way they were originally the ultimate zero-waste garment, made from approx 3 yards of 36” wide fabric, usually cotton. (And here I was a little surprised to see that all five were labelled linen when it was clear only one was and the rest were varying qualities of cotton twill, and there was me thinking the V&A knew its stuff. Literally.) This would be cut into squares and rectangles to make the front, back, shoulders, collars, cuffs, pockets, and gussets.

Early smocks went over the head and were reversible for greater longevity. Later ones might have plackets and a designated front and back, a little more shaping round the neck, and a more modern collar.

‘Mine’ were entirely hand-sewn, some more neatly and carefully than others. A couple were very basic: big stitches, thick threads and knots, visible mending and repair work. But it’s all relative; we rarely see hand-stitched seams and collars and buttonholes, and even these examples look wonderful to my modern eyes.

So the more sophisticated ones are mind-bogglingly brilliant. It’s the very fact that so many people - women, I imagine - were skilled stitchers and smockers making these marvellous, utilitarian, functional, practical garments, yet few - makers and wearers - really valued them or bothered to keep them. Not many examples survive, and yet they were once ubiquitous in the countryside.

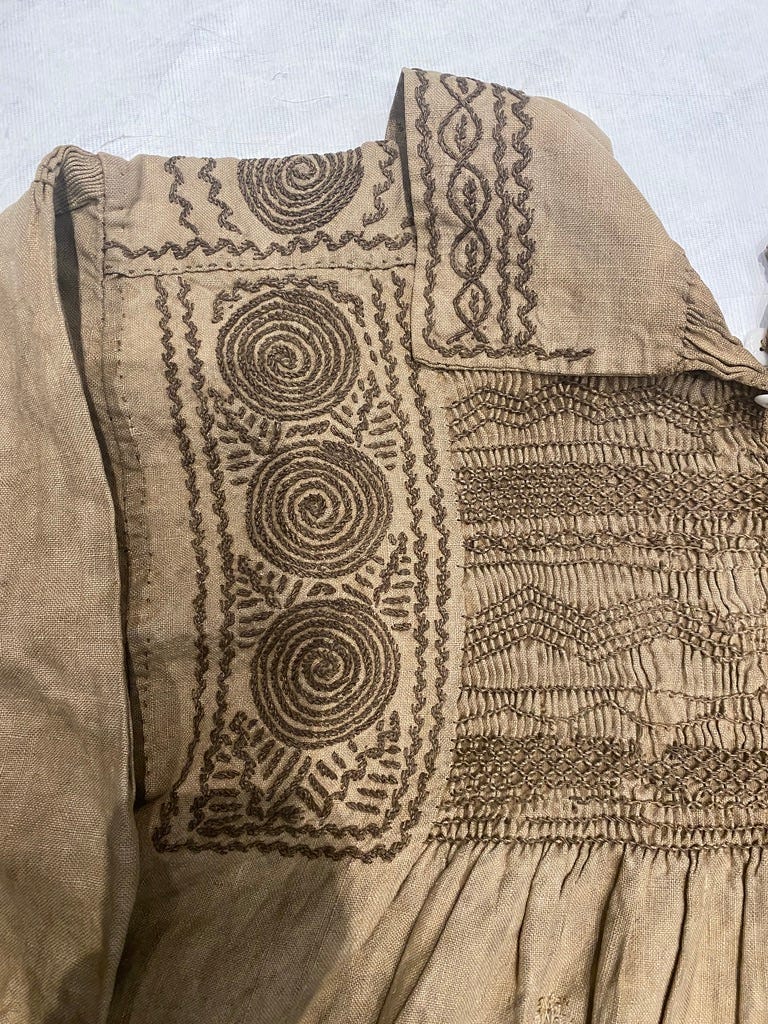

I mean, just look at all this lovely smocking and decorative embroidery.

Someone has sewn line after line of long running stitch which was then gathered, tied, some firmly, some loosely, and smocked using a variety of patterns. Then with chain, feather, stem, rope stitch they have done spiral and flowers and wiggles on collars and shoulders, cuffs and pockets. And every single stitcher has created something unique and meaningful, even if it destined to be worn for doing the muddiest, oiliest, muckiest, most mundane of jobs. All those poor young country boys in their mothers’ best smocks.

I went east and I discovered so much. Mostly that you simply cannot beat seeing things in real life. I’m going back next month for five more smocks.*

Happy Sunday!

*including a blue one. Phoebe asked if they only ever came in drab colours, and yes there were some blue and green smocks, but for really colourful smocks you’d have to go to modern Molly Goddard:

I went a couple of months ago and looked at fabrics woven at the Old Bleach mill where my mother and some of her sisters worked in the 40s and 50s. I felt really emotional looking at fabric designed for use in luxurious settings and woven by teenagers living in rural Ireland.

I went, too! And looked at knitting sticks, knitting samples, and doll stuff. And when I looked at one of the knitting sticks, it was clear to me that it was a nutcracker. So, I asked the helpful person and they said for me to find the item in the collection online when I got home, click the button that allows you to write a note about what's incorrect in the listing, and wait. I did it and, two weeks later, I got an appreciative reply from a curator who also looked at the non-knitting stick and agreed that the record had been wrong since 1912. Now nutcracker admirers have something nice to see and knitting stick admirers won't be fooled into order that object. So, if you've discovered that some of the smock materials are listed incorrectly, they really appreciate your input. With so many objects, they seem grateful for the help. When I went last week, I was told to wear the purple gloves because the cover of the book was "leather." But I quickly realized that the cover was unbleached glazed linen. So, that's going in a note. I LOVE what you chose to see!!! Thank you for sharing these smocks.