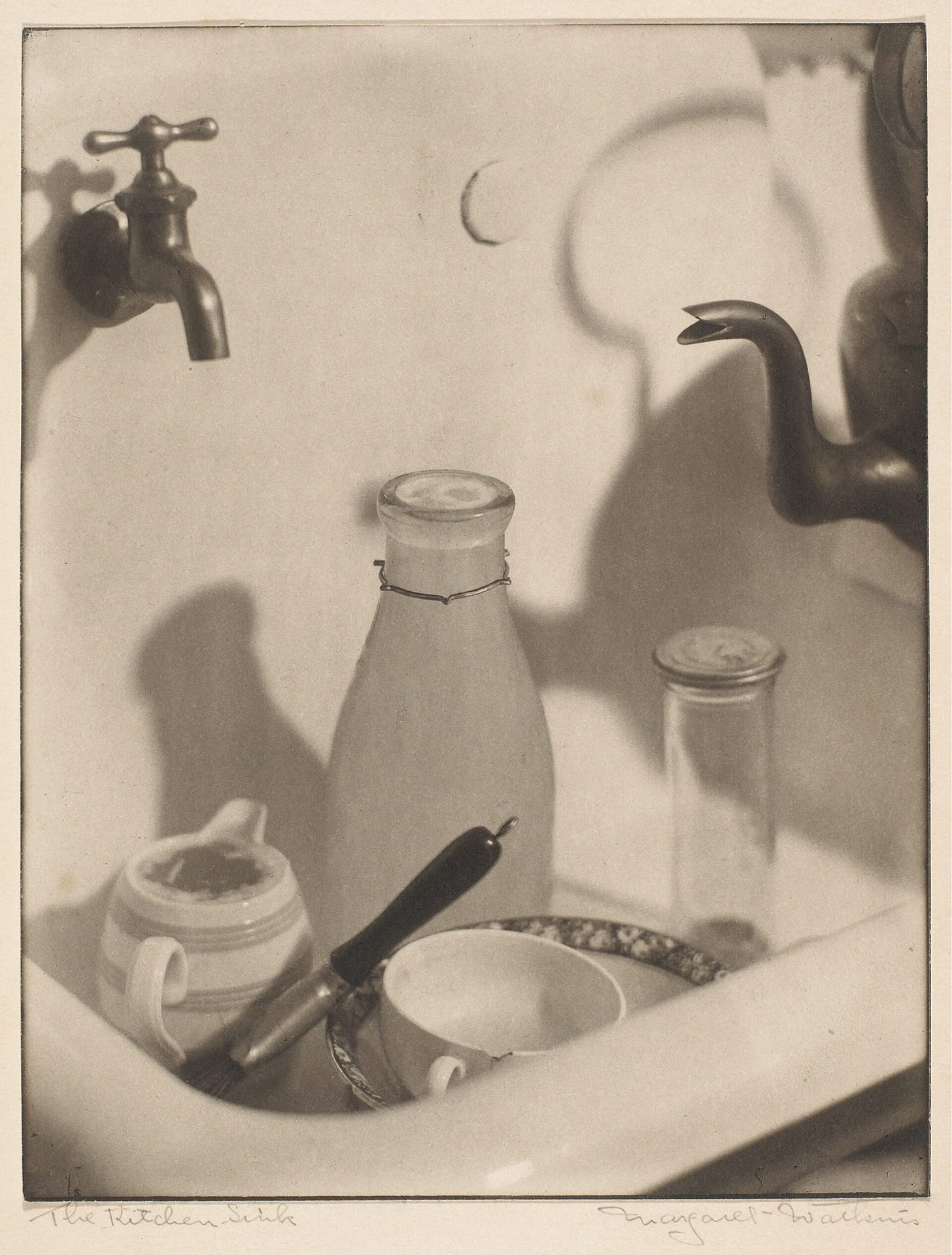

[‘The Kitchen Sink’ (1919) by Margaret Watkins]

I’ve used this photograph before, but I keep coming back to it, fascinated by Margaret Watkins’ work. It contains many of the most important elements of my everyday life - milk bottle, tea cup, jug, tap, kettle - all within a sink.

It’s such a beautiful still-life, that whoever chose it for a Canadian stamp in 2013 must have had excellent taste.

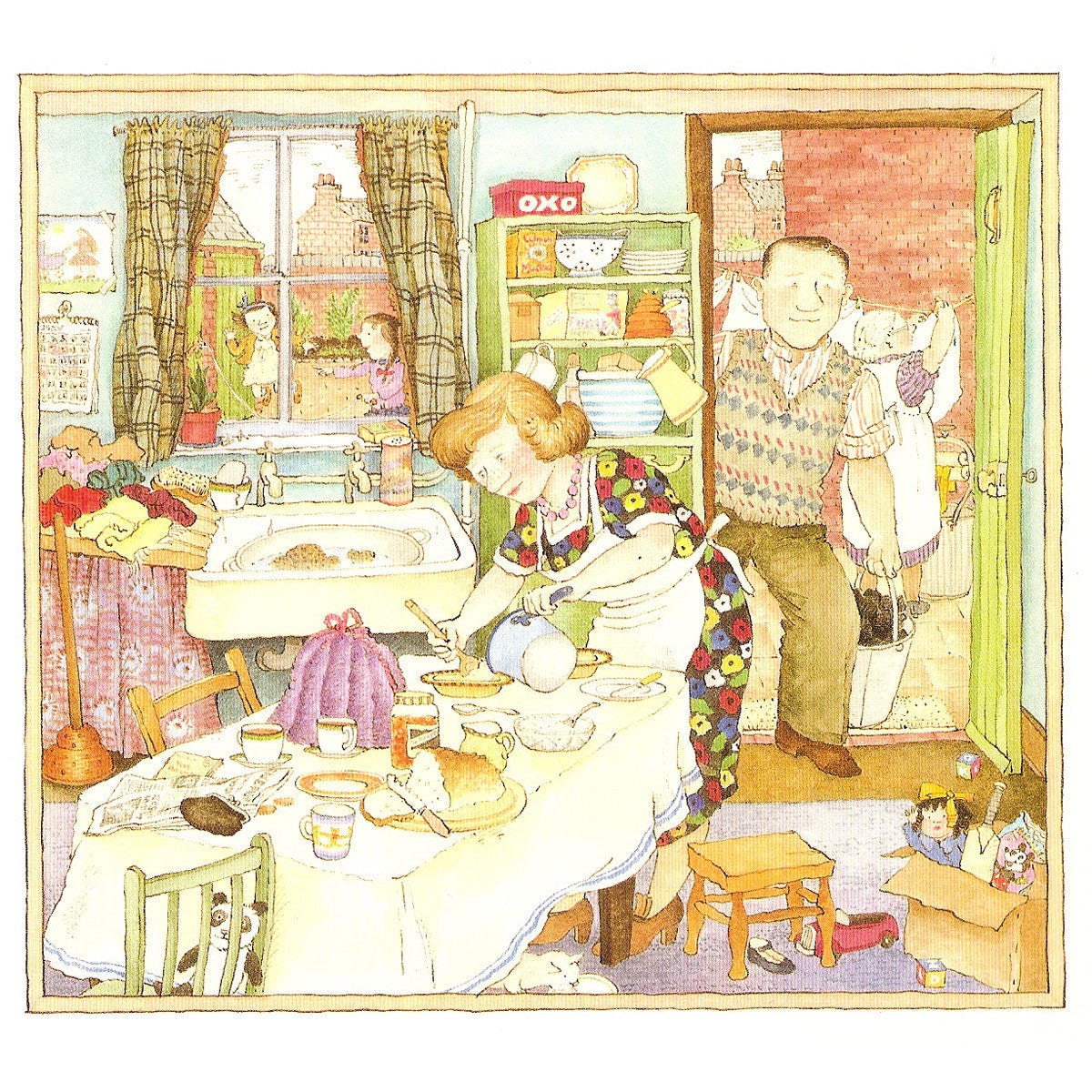

[Queen Mary’s Doll’s House (1924), Windsor Castle]

Although I have no doubt that some people thought the Post Office must have sunk to a new low to feature a sink with all its connotations of dirt, food scraps, scrubbing, scouring, red-raw hands, menial labour, and an endless cycle of household tasks. (Fine to keep it all below stairs, though, and show it in its proper place in a Queen’s dolls’ house.)

[‘The Tiled Kitchen’ (1954) by Harry Bush]

But it shouldn’t be forgotten that, well into the C20, vast numbers of houses still lacked hot and cold running water, sinks and baths, so for millions of people the indoor sink really was transformative. So, by the time the stamp was issued, the sink had long escaped the confines of the kitchen.

[Christ Church in Sheffield, 1950s, by Harry Stammers, my favourite C20 designer]

In the second half of the C20 it even made it into church windows, and became an emblem of gritty realism in art (the Kitchen Sink artists), plays (Kitchen Sink drama), films (A Taste of Honey, Saturday Night and Sunday Morning), television (Coronation Street), and novels (boarding houses with “chipped sinks” in Lynne Reid Banks’ stories).

[‘Kitchen’ (1965) by John Bratby]

At last, it was acceptable -almost - for a sink to be seen, despite millions of households having one. It was still a little unseemly, though, an aspect of daily domesticity and drudgery which needed to be denied or covered up, a bit like underwear on washing lines in back gardens…

…and naked milk bottles on tables. This is from Jeanne Dielman, 23, Quai du Commerce, 1080 Bruxelles (1975) which in the BFI Sight and Sound poll of 2022 was voted greatest film of all time - but I wonder if that was because so many people had been stuck at home for so long during the lockdowns that everyday tedium needed to be recognised. I haven’t seen the film, and am not sure I want to; it goes from washing-up and peeling potatoes to something a lot less domestic.

[sink with washing-up bowl, illustration from Peepo! (1981) by Janet and Allan Ahlberg]

I’ve been thinking about sinks because a little while ago I went into John Lewis to buy a new washing-up bowl and discovered there were none in stock, none coming into stock, and was told that people these days don’t use washing-up bowls. And it’s true, our three children don’t have them, but I simply refuse to accept that washing-up bowls are on their way out. How else do you prevent all your glass and crockery getting chipped (“wash up carefully”, I was told)? How do you rinse things when all the water is mucky and soapy, or carry the bowl to plants to water them, or transport wet clothes to the line without leaving a wet trail?

[‘Kitchen Sink’ (n.d.) by Rosamund Ross (1928-88)]

But, and there’s a big but, many sinks do look really beautiful without a horrible piece of grey plastic squatting in them. I don’t know the date of this painting, but it looks like an institutional or shared sink, a meditation on whiteness and washing and old-fashioned piping (you can almost hear the hammering and rattling when the tap is turned on) and brushes and soap. I like it because it is so washed-out, so to speak. It reminds me of the time when I was ten and was allowed into the room at the end of the children’s ward in hospital and acquired a new word: ‘sluice’, which, admittedly hasn’t been that useful until our last visit to Stockholm and a walk to Slussen (the sluice, or lock).

[‘Still Life with Kitchen Sink’ by Simon Quadrat]

I like this contemporary sink, too, precisely because everything is so plain, so well placed and spaced. It’s the antithesis of a posh fitted kitchen with a double sink and a dishwasher and definitely no wonky taps, but it conveys a nice feeling of self-sufficiency, a reliance on well-loved utensils, and is the epitome of “well-scrubbed”. It’s the kind of sink you’d be happy with in a studio or a holiday home (it says gîte to me).

[‘Washing Cherries’ (1988) by Norman Hollands]

However, there are plenty of sink images which are anything but well-scrubbed. This photograph is fabulously evocative, but I long to get some Vim and a scrubbing brush and attack the dirt.

And where to start with this, a still from Scarlet Street (1945) which is more Nightmare on Scarlet Street for me. It’s a film noir, and this is all the noirishness I’d need to see; my first impulse would be to wash it all up and get it out of the sink.

[‘Helping at Home’ (1961), Ladybird book]

It’s very ironic that I am now this sort of person when once I would have done anything to avoid washing and drying up - the loud arguments with my brother still ring in my ears. Peter and Jane, Janet and John, we most certainly were not.

[(The) Kitchen at Night: 1950 by Patrick Heron]

Washing-up is one of those jobs where the person has to turn their back on the rest of the room and, therefore, a film camera which can immediately create tension, and now I’m racking my brains to think of an example. I’d need to keep the windows uncovered as in this wonderful painting, which frames the sink as the point of action, so that I’d get the reflection of an assailant and then could whip round with a grater or colander or similar weapon…More likely in films is something gross coming out of the plug-hole (Kitchen Sink, 1989) or a waste-disposal horror (I’m unable to name any because I can’t watch scary films, or even look at the list in the link).

[‘Flowers in the Sink’ (n.d.) by Sylvia St George (1881-1950)]

On a less violent note, sinks and flowers are made for each other, and in fact create wonderful arrangements when the flowers spills out of what is in effect an enormous container. I sort out all our tulips in our kitchen sink,

[photo in The Land Gardeners: Cut Flowers book]

and invariably fantasise about having a proper flower room (and someone to grow masses of flowers, please) with a huge ceramic butler’s sink and excellent water pressure in the taps, shelves and shelves of vases and jugs and bowls, and a huge table for all my arrangements.

As it is, our sink is small and made of stainless steel. It is ordinary, practical, easy to clean, holds a washing-up bowl, and still I love it. This is why I like Rachel Roddy’s attachment to her sink -

- she even put it on the cover of her book.

Plus, we are in good company. This is the stainless sink in ‘Mendips’, the house belonging to John Lennon’s Aunt Mimi where he spent much of his childhood. The rather snobbish and judgemental Aunt Mimi probably looked down on old-fashioned council house sinks,

like the one in the McCartneys’ home at Forthlin Road.

Far from it being a case of “everything but the kitchen sink”, for me it’s everything about the kitchen sink.

Happy Sunday!

Husbandly unit and I have differing views on the washing up bowl situation. I favour your perspective, Jane. He, resolutely, eschews them. But he bows to my insistence on a stainless steel sink unit - not for me a Belfast sink that looks cool only on initial installation. I’m wedded to my stainless steel - easy to keep clean, looks as good as it did the day it was put in. Despite having a dishwasher, I still quite like a bit of washing up, looking out into the garden and letting my mind wander. I don’t, however, miss being flicked by the end of a tea towel expertly wielded by one of my brothers when I was a child and they were tea towel adept teenage warriors! That said, I did show my own boys how to do it when they were younger and fighting over the washing up….

Without a bowl, how would you make a tiny pond for a toddler to sail a few ducks, while you shell peas, from newspaper into colander - help, my mother just took charge of the keyboard...